Open: Wed-Sat 12-6pm

Visit

Zoe Barcza: ODRADEK, Microplastic Geologic Time Park

Darren Flook, London

Fri 2 Sep 2022 to Sat 1 Oct 2022

106 Great Portland Street, W1W 6PF Zoe Barcza: ODRADEK, Microplastic Geologic Time Park

Wed-Sat 12-6pm

Artist: Zoe Barcza

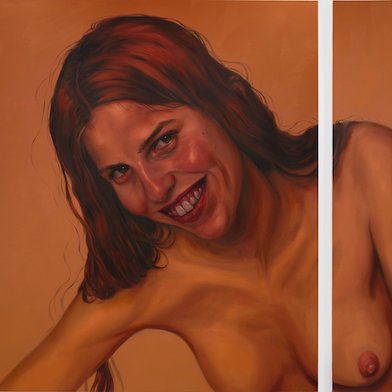

Installation Views

Zoe Barcza (Born 1984, Toronto, Canada. Lives and works between Los Angeles, USA and Stockholm, Sweden). Barcza exhibits three new, large-scale paintings employing her trademark semi-photorealistic airbrush technique and spayed metal flake, the type typically employed by LA car customizers, and a sound work composed by Andrew Zukerman. This is Barcza’s first exhibition with Darren Flook Gallery and it follows her solo presentation at MiArt, Milan in April 2021 with the gallery. Barcza will have a solo project at Frieze, London with Derosia, New York in October 2021.

Text by Olga Pedan

Kafka’s short story “The Cares of a Family Man'' was published in 1919, not long after the end of the first world war and a year before Freud published his text ‘Beyond the pleasure principle’ where he introduced the notion of a death drive. Both texts feature a wooden spool. In Kafka’s story the spool, star shaped and covered in old bits of thread, is an enigmatic being called Odradek that sporadically appears in the family home. A lot has been said about the status and meaning of this wooden spool. Perhaps even more has been said about Freud's wooden spool, which features in a description of a scene from his family life. Freud describes his toddler nephew using a spool with twine on it to play a game of appearance and disappearance that he calls “fort — da”. Freud interprets the game as an attempt by his nephew to gain mastery over painful feelings associated with his mother coming and going. The child re-enacts his loss but positions himself as an active agent of the process, it is as if pain and confusion generate a need to play out the same scenario again, Freud calls this impulse “repetition compulsion”. Often we don’t know what the original scenario was, leading to a feeling of automation — of being compelled to act by something undead inside ourselves.

There is an echo between the two texts in how they address life and non life. Kafka’s narrator says “everything that dies has previously had some kind of goal, some kind of activity that has worn it down, that is not the case with Odradek”. The family man worries that this means Odradek will outlive him. Freud writes “If we are to take it as a truth that knows no exception that everything living dies for internal reasons — becomes inorganic once again — then we shall be compelled to say that ‘the aim of all life is death’ and, looking backwards, that ‘inanimate things existed before living ones’.”

I know that Zoe made the paintings for this show while she was in Los Angeles, a place that seems especially suited to death drive type activities like car crashes and drug abuse. In my cliched imagination it is a place where body culture blurs the lines between animate and the inanimate, I think of golden chiselled chests, eating disorders, plastic surgery and so on. I also imagine it as a place obsessed with repetition, actors enacting endless variations of the same stories and people having automaton-like conversations at parties.

A few weeks into the full-scale invasion of Ukraine I went to see a surrealism show at Tate Modern with my sisters. There were some works I had never seen before that depicted war and revolution. We spoke about how it is strange that surrealism in art became mainly thought of as whimsical and playfully dreamy when it is also the condition of violence and horror. War and large-scale destruction feels surreal. I imagine the effects of climate change such as forest fires and floods feel surreal. It is surreal to think about the liquified remains of ancient organisms being used to fill up a car or processed into acrylic paint and glitter used to make a painting.

The woman depicted decapitated but alive in the paintings is a painter. Two or three of her heads appear in each painting, like sperms or amoeba swimming in primordial art-goo, she looks relaxed. This painter's name is Lucy, like the famous prehistoric hominid fossil. I think she might serve as a distorted full flesh mirror image of Zoe herself. There is a similarity to their names in the kind of surface level banality of sci-fi that hides deeper truths; Lucy meaning light and Zoe meaning life. They could be pretending to be female painters and actually be embodied portals to the destruction of the universe.

Zoe Barcza, born 1984, studied at Stadelschule, Frankfurt, Germany. Recent solo exhibitions include: Haute Speech, Issues Stockholm; Birth Refusal, Bianca D’Allesandro, Copenhagen - both 2021. Nukeface, Bodega (now Derosia), New York, 2020. Goblet, Croy Nielsen, Vienna; Property Sex, Bonny Poon, Paris, France, both 2018. Mother’s Milk, In Extenso, Clermont-Ferrand, France, 2017. DR. AWKWARD, Ghebaly Gallery, Los Angeles, USA; Texas Liquid Smoke, Loyal Gallery, Stokholm, Sweden both 2016.