Two current exhibitions examine the legacy of Francesca Woodman, whose highly innovative and deeply personal work, created between the ages of thirteen and twenty-two, belied her age, while its influence has outstripped the short length of time she was working.

Woodman was born in Denver, Colorado in 1958 to a sculptor mother and a painter father, and her childhood included extended periods in Italy where her art history was bolstered by regular family visits to museums and churches. From 1975 to 1978 she studied at the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) and her artistic life evolved in two principal periods - roughly analogous to her time at RISD (in her late teens) and after that in New York City (having just turned twenty). She would tragically go on to commit suicide in 1981 aged just twenty-two, leaving behind her a legacy both of achievement and potential.

“She knew how to make a good photograph and she knew how to do that at a very young age”

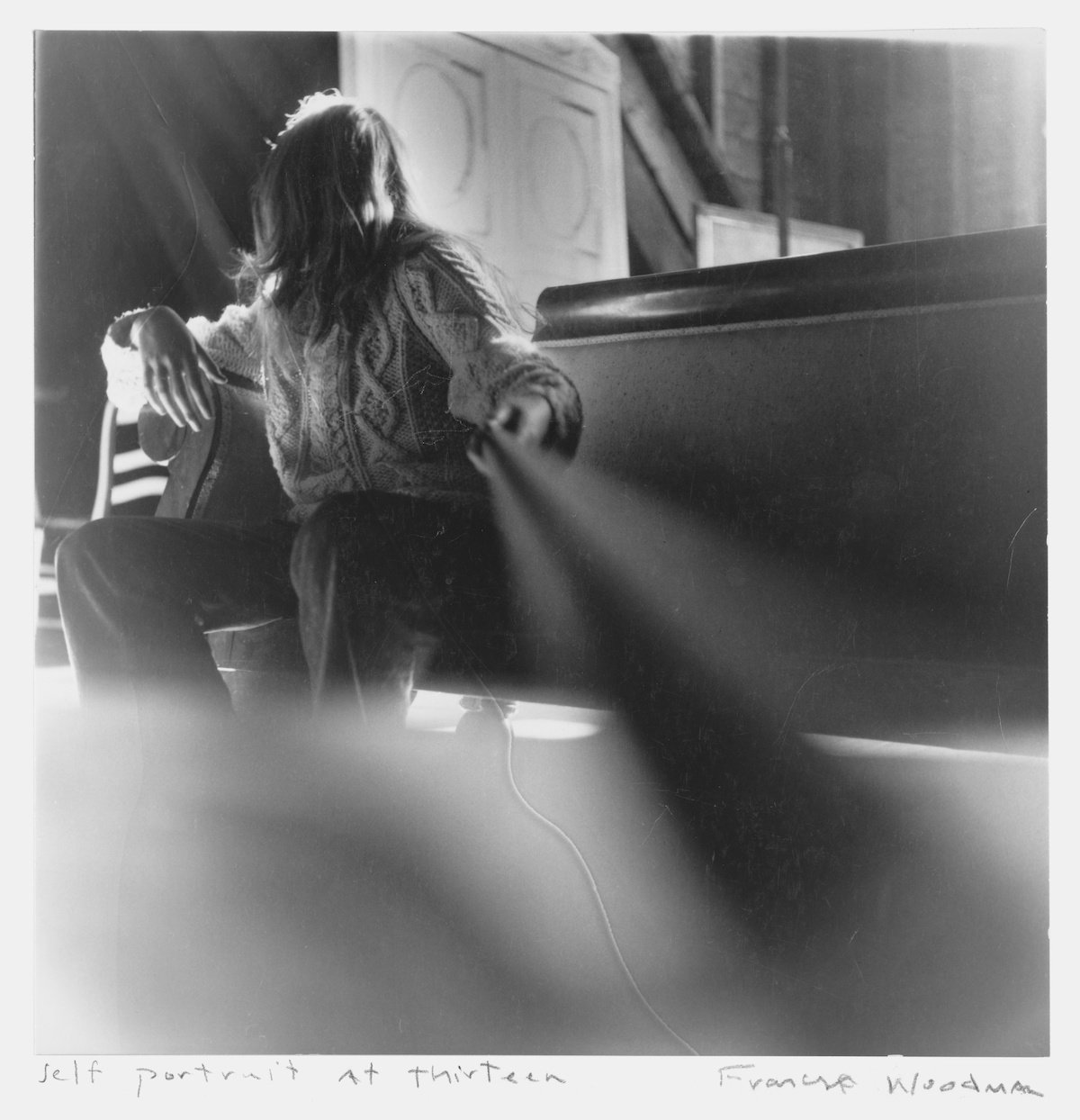

Lissa McClure, Woodman Family FoundationWoodman was in fact just thirteen when she took the remarkable self portrait (below) that is generally acknowledged to be her first artwork - holding the camera far from her body she turns her head away from it and produces a work whose composition, subject, and use of medium point to an understanding far ahead of her years - even the title of the work “Self-Portrait at thirteen” tells us something of the young Woodman with its reference to the similarly-titled 1484 work by Albrecht Dürer.

“she had few boundaries and made art out of nothing: empty rooms with peeling wallpaper and just her figure”

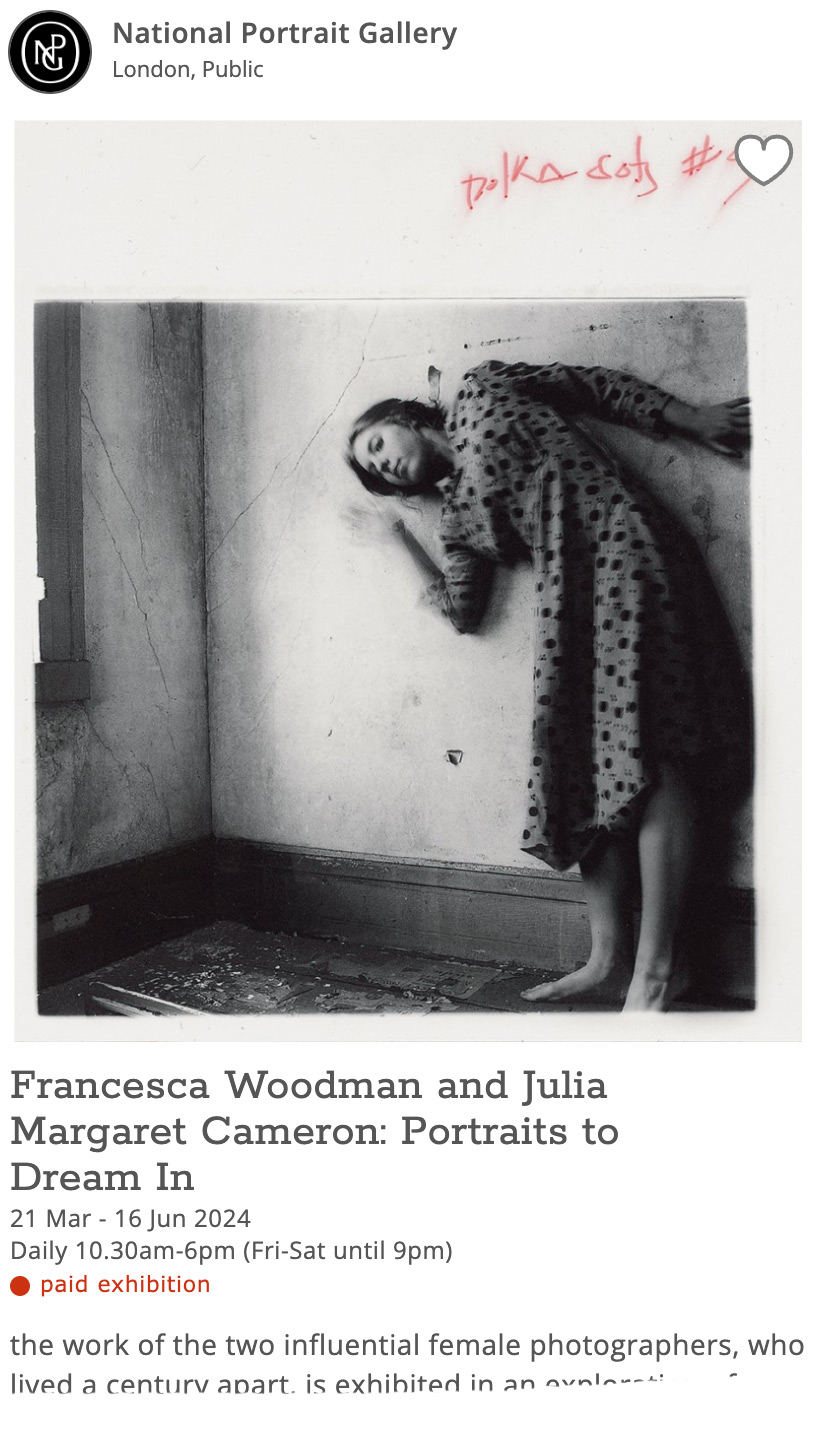

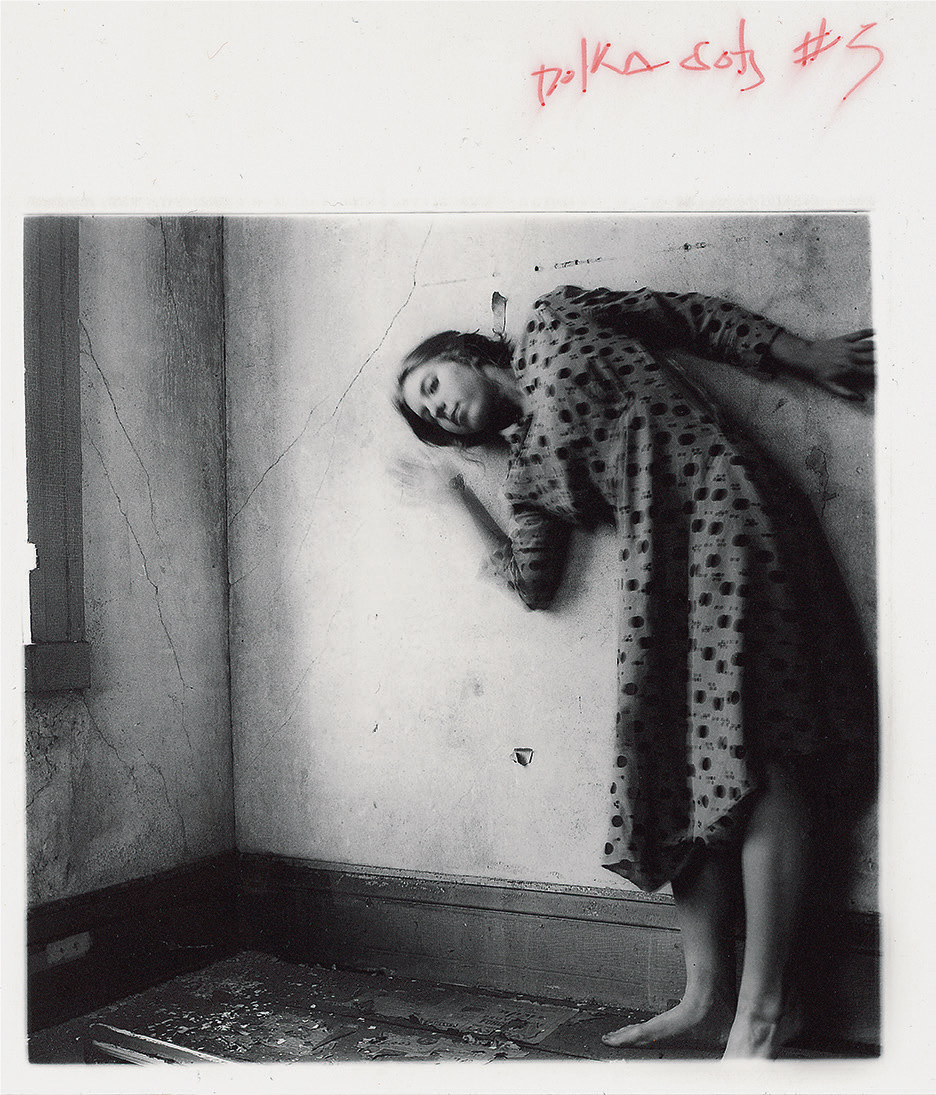

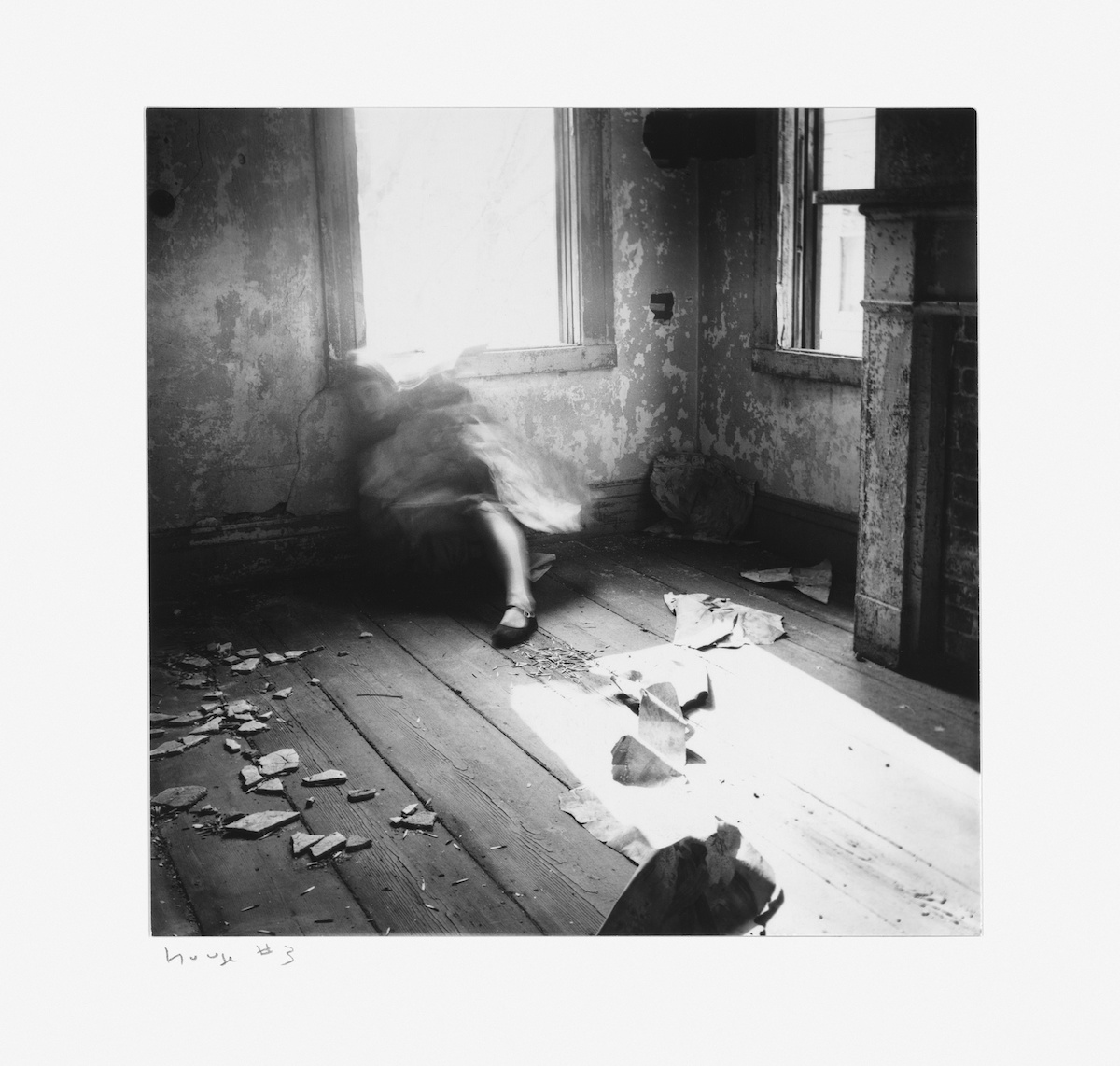

Cindy ShermanThe majority of her work would come a few years later, from her time at RISD, where she showed a seemingly endless ability to produce remarkable imagery - mostly small, intimate, black and white depictions of people and interiors (1976’s “House #3” and “Untitled” from 1979-80 below).

Many of these works are self-portraits (“It’s a matter of convenience, I’m always available” she said) and she is often clearly experimenting, whether with her own body, space, movement, props or interiors. She would also enlist friends and lovers into her work and the pervading sense is of a young artist exploring and examining her world through performative photography.

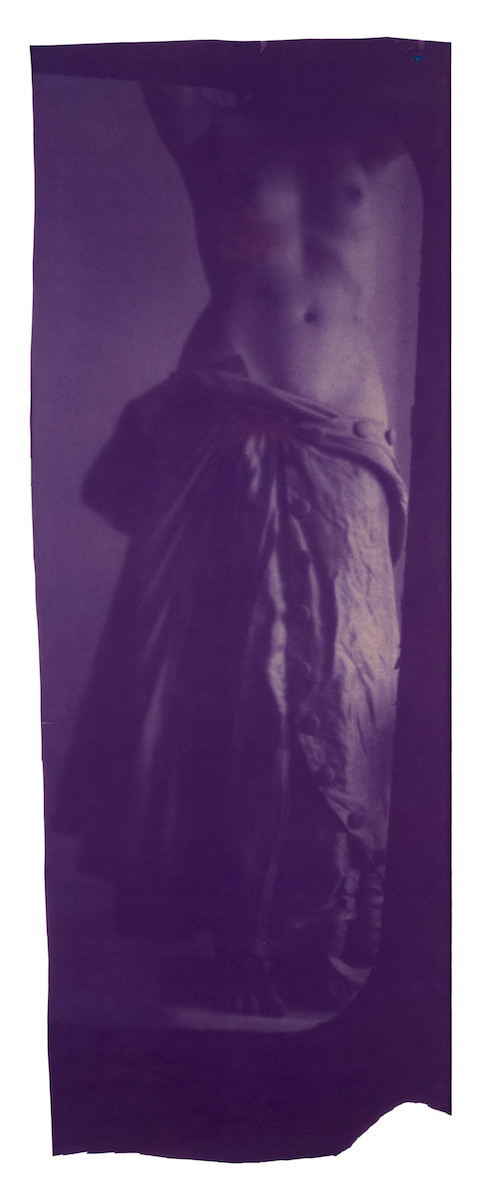

It was following her time at RISD when she was living in New York City that she would go on to produce dramatically different works, not least in terms of their physicality. She was moving from wide-eyed exploration of the world and the body to instead look back to classical architecture, creating at or near life-size “Temple” installation-come-photographs. Using herself and friends as caryatids - the normally semi-clad female architectural supports - she built architectural structures using pictures of actual bodies, pulling the two together in a way that delights, while at the same time seeming perfectly normal.

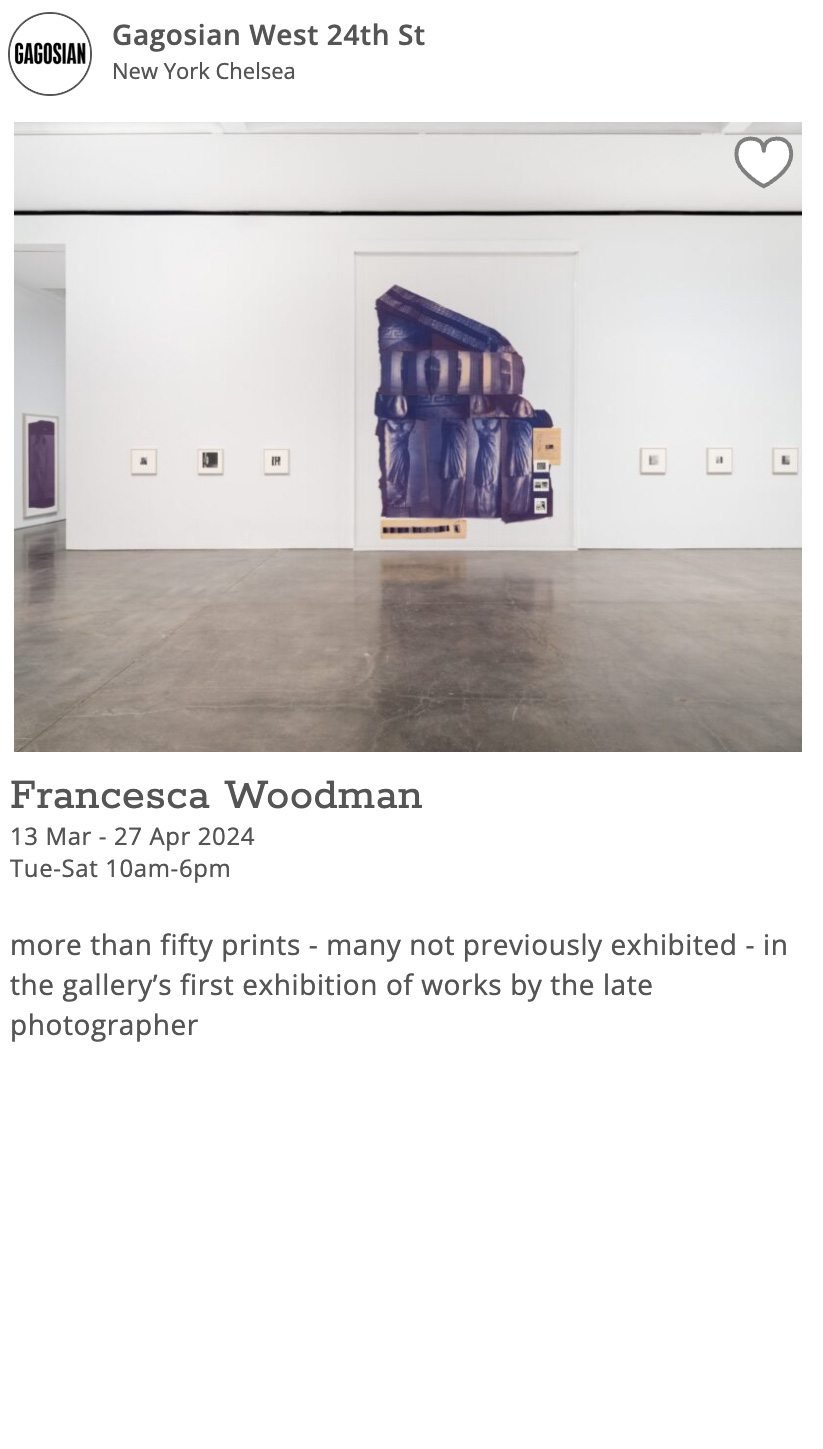

These exhibitions show just how important she is to the history of art and photography. “Francesca Woodman” at Gagosian’s West 24th Street space in New York (above) is a large exhibition which brings together more than fifty prints, all made during Woodman’s life and in many cases not previously exhibited, as well as giving the first public outing for nearly fifty years of “Blueprint for a Temple (II)”, the largest work she produced and a remarkable fusion of her experimental wonder and her ingrained knowledge of classical art and architecture (the work’s sister piece “Blueprint for a Temple (I)” is in the collection of the city’s Metropolitan Museum of Art). This is Gagosian’s first exhibition of Woodman’s work since last year’s announcement of its partnership with the Woodman Family Foundation.

These exhibitions show just how important she is to the history of art and photography. “Francesca Woodman” at Gagosian’s West 24th Street space in New York (above) is a large exhibition which brings together more than fifty prints, all made during Woodman’s life and in many cases not previously exhibited, as well as giving the first public outing for nearly fifty years of “Blueprint for a Temple (II)”, the largest work she produced and a remarkable fusion of her experimental wonder and her ingrained knowledge of classical art and architecture (the work’s sister piece “Blueprint for a Temple (I)” is in the collection of the city’s Metropolitan Museum of Art). This is Gagosian’s first exhibition of Woodman’s work since last year’s announcement of its partnership with the Woodman Family Foundation.

Meanwhile in London, the National Portrait Gallery has a major survey exhibition titled “Francesca Woodman and Julia Margaret Cameron: Portraits to Dream In”, which pairs Woodman with her high Victorian counterpart - presenting Woodman’s early intimate portraits together with a room of the later caryatid pieces, alongside the portraits and tableaux of her predecessor of nearly a hundred years. In this curatorially daring exhibition, the two photographers’ works and themes are directly compared in a side-by-side hang, actively encouraging a cross-appreciation of two of the most influential women in the history of photography.

Cameron’s photographs are well known and rightly admired, Woodman’s undoubted talent is on the way to a wider appreciation and given both the groundwork and where her practice had got to already, one can only be thankful for what she was able to achieve, and imagine what she could have gone on to do.

“as close to a true saint as the putatively secular world of contemporary art can claim … too purely an artist for this muddy world”

Ken Johnson in the New York Times

Polka Dots #5 by Francesca Woodman, 1976, Gelatin silver print. Courtesty Woodman Family Foundation © Woodman Family Foundation / DACS, London; Self Portait at Thirteen by Francesca Woodman, 1972. Courtesty Woodman Family Foundation © Woodman Family Foundation / DACS, London; House #3 by Francesca Woodman, 1976. Courtesty Woodman Family Foundation © Woodman Family Foundation / DACS, London; Untitled, c. 1979-80 © Woodman Family Foundation / ARS, New York. Courtesy Gagosian and The Woodman Family Foundation; Installation view, Artwork © Woodman Family Foundation / ARS, New York. Photo: Owen Conway. Courtesy Gagosian; Untitled, 1980 © Woodman Family Foundation / ARS, New York. Courtesy Gagosian and The Woodman Family Foundation