How do you deal with trauma? What can you do when life throws everything at you - taking away your loved sibling, refusing you the support structure of the family, showing its worst aspects in an seemingly unstoppable cascade of tragedy?

Nan Goldin’s “Sisters, Saints, Sibyls” is a meditation on just such a situation, or indeed succession of situations, taking us through her life and very specific experiences - including the principle focus of the piece, Nan’s older sister Barbara Holly Goldin.

“There is much evidence that it is not Miss Goldin who should be in hospital, it’s Mrs. Goldin” - doctor’s report on Barbara GoldinBarbara was seven years older than Nan and from an early age developed a difficult relationship in particular with their mother, who was herself a difficult person and with whom she would regularly have stand-up slanging matches. Barbara was sent to a psychiatric institution at age twelve, and was to die by her own hand a mere six years later having been let down both by her parents and by her doctors.

Losing her sister would be one of the defining moments in Nan’s life.

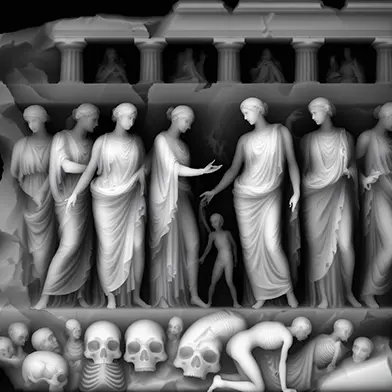

Goldin employs a triple projection screen for “Sisters, Saints, Sibyls” echoing the altar triptychs of religious iconography and showing a myriad of images guiding, explaining, showing, memorialising her sister, her friends, and herself.

The presentation is the second of the Gagosian Open series of off-site projects showing special art in special places and is at the Welsh Chapel hard by London’s Soho, the notorious nightlife quarter of the city, an almost too-perfect setting for a work which starts with a Christian martyr and is made by the same hand as “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency” - the work for which Goldin is perhaps best known and one which also had its first incarnation as an extended slideshow set to music.

The work itself starts with the story of Saint Barbara, the early Christian saint and martyr whose father tortured and ultimately killed her for transgressing the family’s pagan beliefs when she embraced Christianity. A direct parallel is then drawn with the story of Nan’s Barbara, whose rebellious actions provoked the outrage and enmity of her family, leading to her incarceration in a series of institutions and, in all likelihood, her suicide. Nan idolised Barbara and the loss would propel Nan into her own world of defiance, dependancy, and pain - the ups and downs of which the third section of the work unflinchingly portrays.

“Somebody told me recently that my work averted their suicide ... If I can help one person survive, that’s the ultimate purpose of my work” - GoldinGoldin is of course now equally well known for her crusading work in connection with the US opioid crisis and in particular for pursuing the Sackler family, something which further demonstrates her remarkable ability not just for resilience - how many times was she let down by institutionalised medicine after all - but also for action.

Not all art needs to have a reason, and not every artist wants to effect change, but Goldin has a magical ability to make work which is striking and moving, whilst at the same time steeped in activism.

At thirty minutes, this immersive collection of stills and videos, set to a soundtrack including Nick Cave, Leonard Cohen, and as Goldin calls him “the incomparable Johnny Cash”, is hard both on the emotions and on the senses, yet it is beautiful and in a strange way filled with hope, perhaps because hope is the only way to sustain the onslaught.

In the end though “Sisters, Saints, Sibyls” is above all a eulogy to Barbara.

installation view artwork: © Nan Goldin - photo: Lucy Dawkins Courtesy Gagosian