Open: Tue-Fri 11am-6pm, Sat 12-5pm

Visit

Eccentric Spaces

The Artist Room, London

Wed 11 Jan 2023 to Sat 4 Feb 2023

20 Great Chapel Street, W1F 8FW Eccentric Spaces

Tue-Fri 11am-6pm, Sat 12-5pm

One of the great uses of painting is to give hints of a place after we have left it, or to teach us about it while we are in it by showing what it meant, tried, or wanted to look like, giving a purified ideal version the reality only hints at. Paintings tell us what to look for in the streets and vice versa, reflecting on each other till the alternation seems the most productive procedure and we follow a closing avenue of comparison, seizing the coincidence more and more unerringly.

— Robert Harbison, ‘Cities Dark Places: City Planning and Built Worlds’ in Eccentric Spaces (1977: MIT Press), p.62

The Artist Room presents Eccentric Spaces, a group exhibition including works by Leonard Baby, Anderson Borba, William Brickel, Eiko Gröschl, Justin Rui Han, Martin Kippenberger, Graham Little, Iva Lulashi, Fleur Patrick and Francesco Pirazzi.

This exhibition takes its name from Eccentric Spaces (1977), a celebrated publication by architecture critic Robert Harbison (1940-2021). Defying conventional scholarship and trends of its period, he didn’t focus on theoretical discourse or the contemporary geometry of modern and postmodern buildings. Instead, Harbison explored how spaces from historical to present – gardens, rooms, buildings, streets, museums, maps, fictional topographies, and architectures – can be more interestingly understood in terms of the sensitive and real ways that humans create, occupy, change, and abandon them. What interested Harbison was not necessarily the new, but the unique way in which interior and exterior spaces change in appearance, motive, use and cognition over time; how spaces are often the products of many different periods and movements simultaneously.

Divergent case studies abound. From the ‘unmistakeable effrontery’ of Jean Dubuffet’s seminal white plaster playground in Holland; to the ‘cerebral’ importance of snow in Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s paintings; or the haunting, nightmarish environments in Franz Kafka’s novels he describes as ‘mysterious, truthful’ settings ‘impos[ing] on us by their squalor,’ Harbison dissects how artists manufacture idiosyncratic – eccentric – spaces. Harbison indicates how artists have the unique capability to show both internal and external architectures in ‘more perfect use than can be met in actuality, imagining just the right life to go with [them]’.

Thinking with and through Harbison’s poetic and expansive notion of the Eccentric Space, The Artist Room’s exhibition asks viewers to consider nuanced sensibilities of space in the works of an intergenerational group of artists from across Europe, the United States and Latin America. From conjuring forgotten memories to envisaging worlds outside our own, the show seeks to highlight painting and sculpture’s eccentrically evolving force. Asking how and why we enjoy getting lost in different spaces, the show seeks to illuminate how artists continually evoke spatial allegories and provide new beginnings. Key is the importance of imagination in defining our lived experiences and reading the works on view. ‘Dreaming the fantastic is not enough,’ Harbison stresses. ‘It must be lived.’

Synthesising aesthetic languages of Impressionism, Post-Impressionism and Pop, Leonard Baby’s (b.1996, Colorado) research interests span femininity, androgyny, identity and feelings of otherness. The Face You Make When It's Time To Go (2022) borrows its composition from Possession, a Polish psychological horror drama film from 1981. ‘I chose this specific composition because of its ambiguity. It reminds me of Wyeth's Christina's World; total peace and urgent desperation existing in one figure,’ Baby observes. ‘The architecture framing the figure creates a cold and domestic feeling, which is something I especially love about Eastern European films.’

The spaces depicted in William Brickel’s (b.1994) oil paintings are at once familiar and imagined. Depicting figures that reference the artist’s own personal history and relationships, his paintings speak to the broad yet personal ways that spaces we occupy in our youth can define our outlooks on the world in later life. Often depicting figures with elongated bodies, hands, and feed, Brickel has observed his intention to convey emotional vulnerabilities to encourage sympathetic readings from the viewer.

Anderson Borba’s (b.1972, Santos, Brazil) practice includes techniques of carving, burning, and varnishing in addition to perforating with saws, chisels and blowtorches. Partly influenced by self-taught Brazilian sculptors, the artist creates works with a strong sense of presence and physicality – often on a human scale. Ms. Peanut (2022) incorporates magazines pasted and pressed onto the surface until the point where they become blurred and illegible. Blurring distinctions between macro and micro, natural and synthetic, Anderson describes how this unique collage process is unstable and unpredictable.

Largely depicting landscapes, Eiko Gröschl’s (b.1992, Graz, Austria) paintings evoke feelings of isolation; conveying the sublime experience that vast open spaces can conjure within us. Describing View From Inside "The Car" (Mittel) (2022), Gröschl noted his intention to convey a ‘hybrid between the real and the felt’. A synthesis of real, lived experiences with hazy scenes drawn from dreams, the painting situates an abandoned building in the rolling hills of Italy’s countryside alongside an ominous aeroplane in the distance.

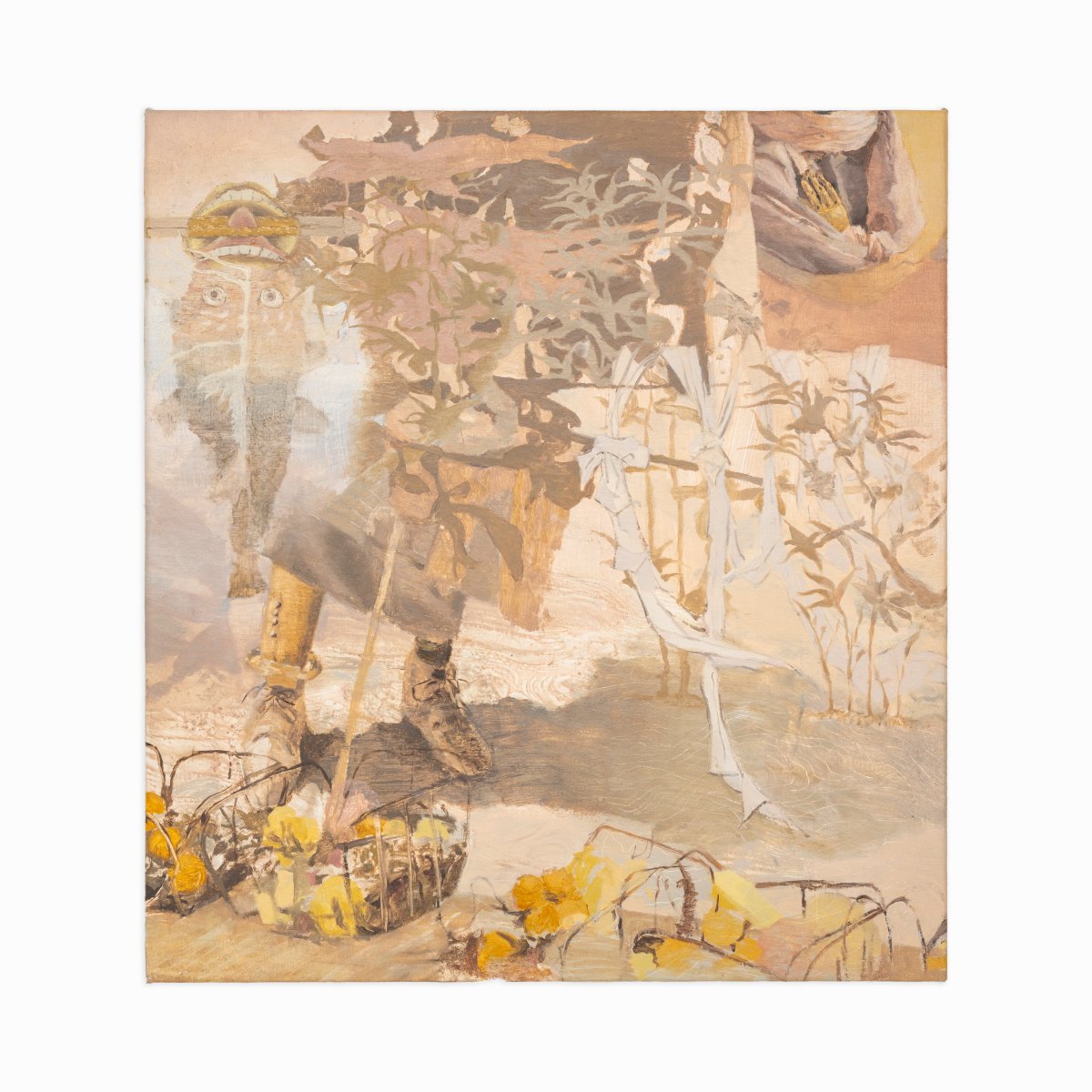

Pre-existing spaces found in film stills often function as a starting point for Justin Rui Han’s (b.1999, Rochester, New York) paintings, which incorporate subject matter that links his East Asian heritage with life in the West. Linguere's Courtyard (2022) references Hyenas, a 1992 film about a woman returning to her hometown in Senegal, looking to exert revenge on a man who married her in her youth and later abandoned her with their child. Referencing the relationship between international finance and colonialism in such parts of Africa, the film mirrors Han’s interest in reflecting ‘back and forth dynamics; pictorial decadence and the historical depravity that [such] decadence can go hand-in-hand with.’ Han’s interest in collage is also evidenced in the placement of an overlain fish that was found in a Chinese manuscript of marine curiosities, creating a ‘hybrid space where things can coexist and challenge each other.’

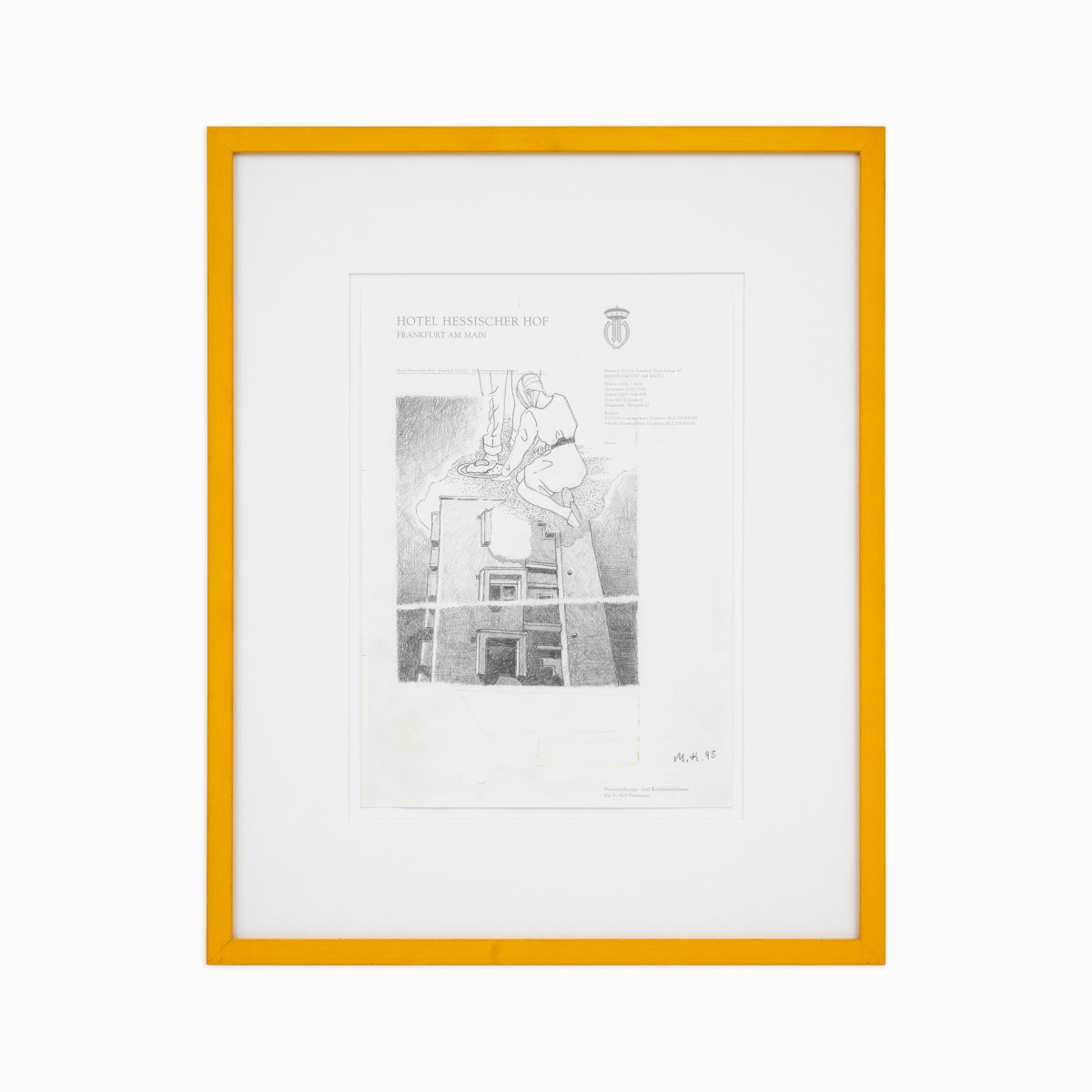

Martin Kippenberger (b.1953, Dortmund, Germany; d.1997, Vienna, Austria) was an experimental and prolific artist who defined postmodern artistic discourse in the 1980s. Untitled (Hotel Hessischer Hof, Frankfurt am Main) (1995) from Kippenberger’s expansive drawing series produced on paper collected from hotels he visited across Europe and America. Expressing whatever fleeting ideas were passing through his conscious, they are often described as his most intimate works and a cumulative ‘autobiography in sketches’.

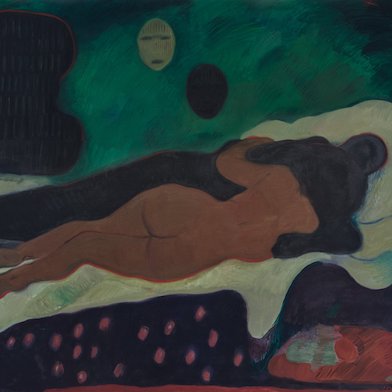

Born in Albania but based in Italy since childhood, Iva Lulashi’s (b.1988, Tirana, Albania) practice departs from a concern with the communist political landscape of her birthplace – and the strange tensions that lie within constructed imagery and propaganda. Also often deriving from found video footage, Lulashi’s recent works have been exploring voyeurism, dissecting tensions between public and private. Sometimes depicting intimate scenes in wild landscapes, Lulashi has observed that ‘Eroticism is everything, it's not the act. It is tension, a relationship that certainly passes through bodies, but which also concerns our relationship with the environment.’

Graham Little (b. 1972, Dundee, UK) has described his practice as ‘about the vulnerability of being human’. Drawing reference from a vast archive of lifestyle and fashion magazines, his meticulously produced gouache paintings on paper render figures amongst elaborate, semi-fictitious, perhaps utopian settings. In Untitled (Mountain) (2021) a man peeps behind a large, curved window looking onto a sublime mountainscape. Cinematically gazing toward a distant figure, the tension in his poise seems at once blissful and apprehensive.

Fleur Patrick’s (b.1979, New Zealand) paintings arise from a process of erasure; of wiping paint around and away from their surface. From her Glass Curtains series, the works reflect Patrick’s interest in the theatre of painting and how curtains hold ‘connotations relating to enclosure, containment and defining space’, also stemming from the Latin word ‘cohors’, which means courtyard. The founds spaces she depicts are non-specific yet symbolic structures. Describing the graphite grid frameworks, she says ‘they are all about the meeting of things, they are rigid, structured, straight and solid.’

Francesco Pirazzi (b.1994, Alatri, Italy) depicts isolated – perhaps melancholic – scenes. Predominately situated at nighttime, and never rendering any human figures, in works such as Nascoto (2021) the artist pays particular attention to the contrast and direction of light – in a manner that references surrealist artists such as René Magritte. Light can provoke an abstract experience that is ‘truer than truth,’ Pirazzi has observed.