Open: Tue-Sat 11am-6pm

Visit

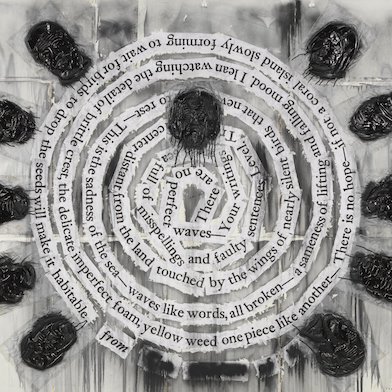

Phantasmagoria

lbf contemporary, London

Artists: Caroline Absher - Grace Bromley - Connie Harrison - Cheung Tsz Hin - Antonia Caicedo Holguín - Yowshien Kuo - Jack McGarrity - Fabian Ramírez - Kristian Touborg - Jiajia Wang - Kate Pincus-Whitney - Tianyue Zhong

I seize the sphery harp. I strike the strings.

At the first sound the golden sun arises from the deep...

The echo wakes the moon to unbind her silver locks,

The golden sun bears on my song

And nine bright spheres of harmony rise round the fiery king . . .

WILLIAM BLAKE, ‘Enitharmon Revives with Los’

The etymology of the word ‘phantasmagoria’ stems from phántasma (“ghost”) + agorá (“assembly”). A gathering of spectres. Many of the works on display in the present exhibition, by artists working across three continents, bear the traces of the past’s incisive presence, and of successive breakthroughs in art history reimagined anew, like ghosts in our own time. ‘Poetry survives because it haunts and it haunts because it is simultaneously utterly clear and deeply mysterious’, wrote Nobel Laureate Louise Glück, and ‘because it cannot be entirely accounted for, it cannot be exhausted.’ The artists assembled here paint like Glück’s brief for the poet. These works are at once clear and mysterious, truthful yet arcane. In their eclecticism of forms, the gathered paintings oscillate between figurative imaginings of leisurely landscapes and idle objects, sonorous distributions of abstract paint, and the human body trapped in liminal spaces between dreamscapes and waking life. Spurred the imaginative power William Blake expressed in his ‘prophetic books’, according to which the texture of dreams was not mere fantasy but an essential part of life, this group of artists address the world of forms that meet at the threshold between the cold light of experience and the wildness of dreams.

In her polychromatic visions of remembered landscapes, Connie Harrison’s compositions smoulder in flickering patchworks, revealing dense mark-making from scraped oil and wax which blur the distinctions between the magnified flowers in the foreground and the wild vegetation beyond. The palette and layered brushstrokes share something with Claude Monet’s enigmatic late period, and his gestural reworkings of his Japanese water-lily garden at Giverny; the title, Leaves to blossom, fall to nourish captures that pendulous flow of seasonal transformation. Elsewhere, in a riotous still life-cum-collage, Kate Pincus-Whitney incorporates weighty tomes by Hilma af Klimt and Aldous Huxley, artistic forebears who sought to represent the fantastical worlds of the imagination unbound by corporeal function, alongside Bacchanalian treats like a bottle of St. John’s 2012 Bourgogne and fresh lobster. Ritual Union: Hecate’s Garden (Faith in a Seed) (2024), which refers to the Greek goddess of magic and necromancy and who was the inspiration for Blake’s character Enitharmon, is a garden of earthly delights lost to modern excess. Elsewhere, middle-aged holidaymakers cavort, exercise, and stare at one another in an arcadian dream in Antonia Caicedo Holguin’s oil-on-linen Day Dream (2023), which reimagines Paul Cézanne’s bathers in a halcyon scene of middle-aged abandon to leisure. A Sidelong Glance (2023) might depict a millennial cast of characters instead, but there remains a timelessness to the hazy play of grassy verge and baby-blue sky, as though this is what we might imagine paradise looks like – if in paradise we retain the worldly desire to control how we present ourselves and a capacity for relentless self-scrutiny.

As such, another way of thinking about the phantasmagorical nature of image production is to recognise the disjuncture between dream and reality, between the false floods of desire and the murky truths that lurk behind the beatific facade. Jack McGarrity’s Package Deal (2024) takes on this subject. Like Caicedo Holguin, McGarrity depicts an idyllic sojourn: here, tourists on a precarious vessel astride glistening Greek isles, as wildfires pump smoke into paradise. Interspersed with collaged strips torn asunder and the surface lightly sanded, the water shimmers with the incandescent luminosity of a saint’s day parade, while the bunting stretches out wet and damp. Nothing is as it should be. The same is true of Yowshien Kuo’s acrylic and leaf foil Ra Ra Return! (2024), in which three young friends repose on quilts in a nocturnal field of blue barley while six black horses stand guard or else plan an assault on the unsuspecting idlers. The composition is a total environment of the artist’s imagination: real in the sense that each part is true to life yet inconceivable as a whole, and so feels as though seen through a lucid dream. Two works by Fabian Ramirez, Dreaming of the Serpent (you) and Dreaming of the Serpent (me), position our perspective above two nude figures, each of whom are reclined in a duvet and seduced by serpents. A modern reimagining of the Genesis myth, Ramirez’s diptych encapsulates the dangers and the gratifications of temptation: these are visceral paintings of human bodies having lost a grip on their reality.

If some artists have approached the subject of imagined, remembered, or invented landscapes, then others avail themselves with abstract topographies to examine the ways in which painting (and, perhaps, painting alone) can depict the non-physical, timeless, and unchangeable essences of forms. In Grace Bromley’s Vital Heat (2024), it is as though we see a rendering of high temperature spatialized onto the canvas. The conflation of oblong, arching, and ovoid forms force themselves in space, integrating and dissolving with one another, while impossibly thin white lines radiate a sense of heat and movement. Similarly, Jiajia Wang’s Tree#90 Hot (2024) is also interested in the degree of heat or intensity invested into abstract shapes, and depicts a hallucinatory universe of smudged boundary lines and interwoven diagonals. It is a chaotic but effervescent composition that nevertheless speaks to the Blakean maxim of art’s purpose: to ‘work up imagination to the state of vision.’ In Fuel (2023) by Tianyue Zhong, we are confronted by an altogether different emotional temperature. Recalling the abstraction of Joan Mitchell and Zou Wou-Ki, and rendering the abstract but existential burden of resource extraction with a scrawled surface that manages to be resolved and equivocal at the same time, Zhong has found an expressive vocabulary to deal with our collective nightmare with a singular touch.

For other artists in Phantasmagoria, the human body is hauntingly present but defamiliarised like a spectre projected against a wall of shadow. Inspired by the experience of false awakenings, or a vivid dream about awakening from slumber, Cheung Tsz Hin’s Dream Within a Dream (2024) conjures up the quality of seeing the mathematical wonders of the natural world up close––a dendritic pattern on a frozen lake, for instance, or the balmy marks that bees leave in an apiary––before we see the frightening presence of a human arm and a leg, as though a body trapped is under a tinfoil avalanche. In Caroline Absher’s oil, Face of the Wind (2024), the whirring energy scatters pastel pinks and oranges across the canvas as the faint outline of a head and torso with whirling red forefingers pointed at the ground appears lost in a haze of purple ticker tape. A similar sense of the human form lost to reality can be identified in Kristian Touborg’s two enigmatic dreamscapes: Sheltering a Burning Hope from the Foolish Fire we Started and Intangible Grasp (both 2023). Illuminated in white like the shadow play of the Victorian magic lantern (or the fantasmagorie, which projected friezes of skeletons, demons, and ghosts, onto walls, smoke, or semi-transparent screens to create a séance-like atmosphere), the figure in Intangible Grasp is animated by an otherworldly aspect. Could the ‘intangible grasp’ refer to the insubstantial grip that we have on our realities? Might this painting, and indeed all of the paintings on show, be about the paradoxical requirement for us to abstract our senses in order to see the world more clearly? Like Blake with his sphery harp before them, these artists relish in the joys of mark-making to ask more of us at a time when realities have never been harder to accept, and the need for new ways of expressing our changing relationship to the world more urgent.

–Matthew James Holman