Open: Mon-Sat 10am-6pm

Visit

Arturo Vermi in the Space-Time Continuum

Brun Fine Art, London

Tue 12 Oct 2021 to Fri 10 Dec 2021

38 Old Bond Street, W1S 4QW Arturo Vermi in the Space-Time Continuum

Mon-Sat 10am-6pm

Artist: Arturo Vermi

Arturo Vermi in the Space-Time Continuum is part of the tightly focused series ‘Perspectives’, the aim of which is to take a close look at some of the themes and techniques that characterised, for a certain period, the production of artists that have already been represented by Brun Fine Art in the past. The exhibitions takes place in the London gallery from 12 October 2021, featuring around 20 artworks by the Italian artist.

Artworks

Sequoia, 1980

Tempera and gold leaf with engraved signs on curved wood

900.0 × 1480.0 × 150.0 mm

Isola, 1973

Acrylic, graphite and collage with gold leaf on a curved, arched panel

1000.0 × 850.0 × 50.0 mm

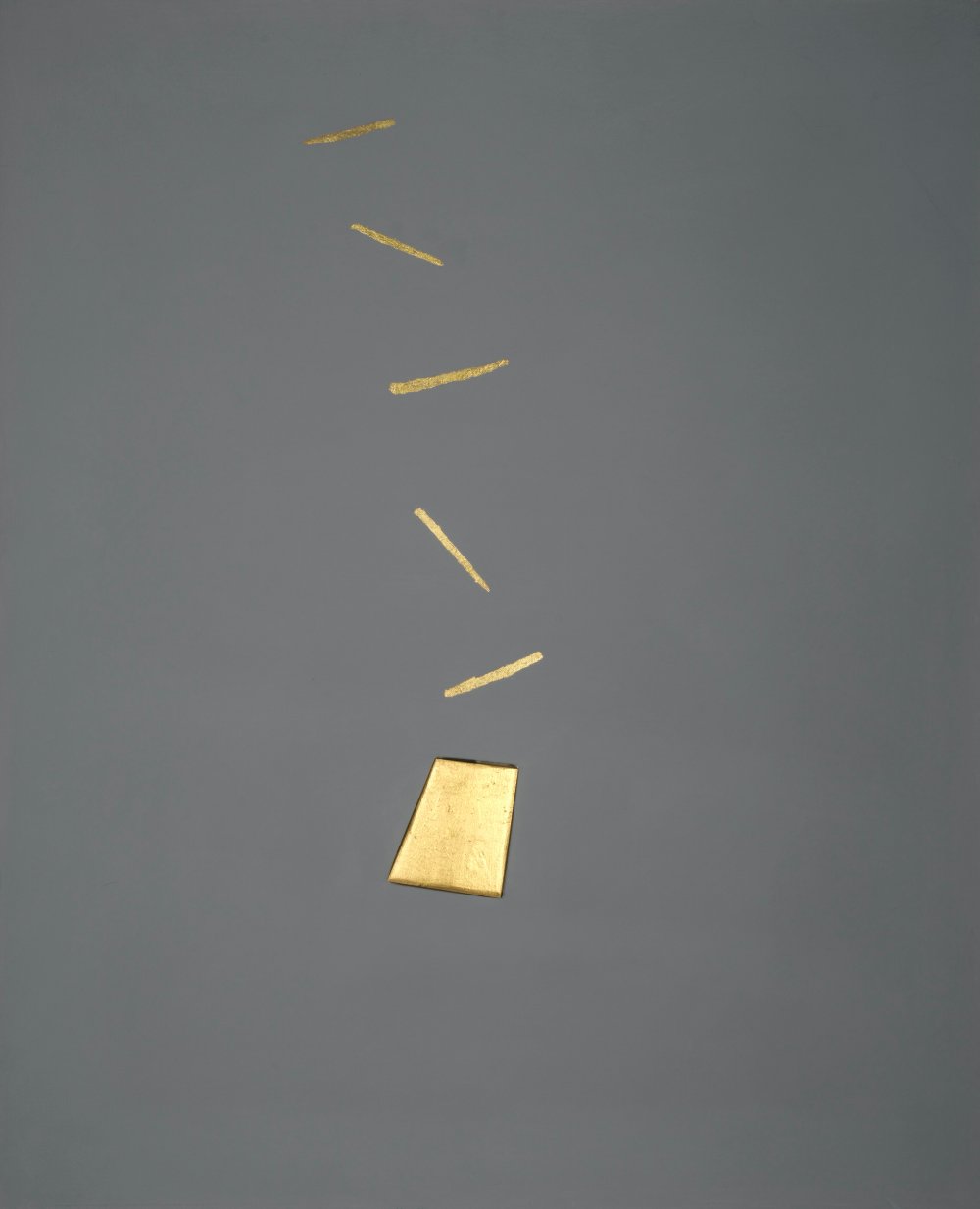

Piattaforma, 1974

Graphite and gold leaf on curved panel

970.0 × 1600.0 × 45.0 mm

Registered at Archivio Arturo Vermi under "S37R150216S-753"

Piattaforma, 1976

Signed and dated, on the upper left of the verso: “Arturo Vermi / 76” Illegible writings on the top right corner. Registered at Archivio Arturo Vermi under “R67S110603S-1149”

Luna, 1975

Silver leaf on board

570.0 × 202.0 × 360.0 mm

Registered at Archivio Arturo Vermi under “N57L130302F-1261”

Reperto, 1983

Collage of electric circuit and gold leaf with signs engraved on marble

560.0 × 440.0 × 100.0 mm

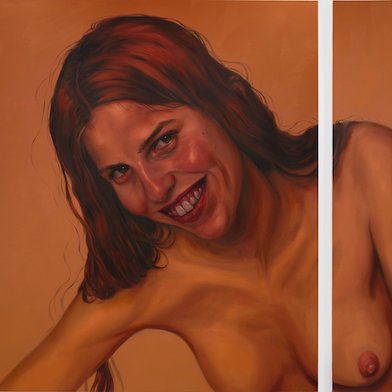

Invasione, 1975

Acrylic, gold and wood on canvas

800.0 × 1000.0 mm

Registered at Archivio Arturo Vermi under “N57P300602S-909”

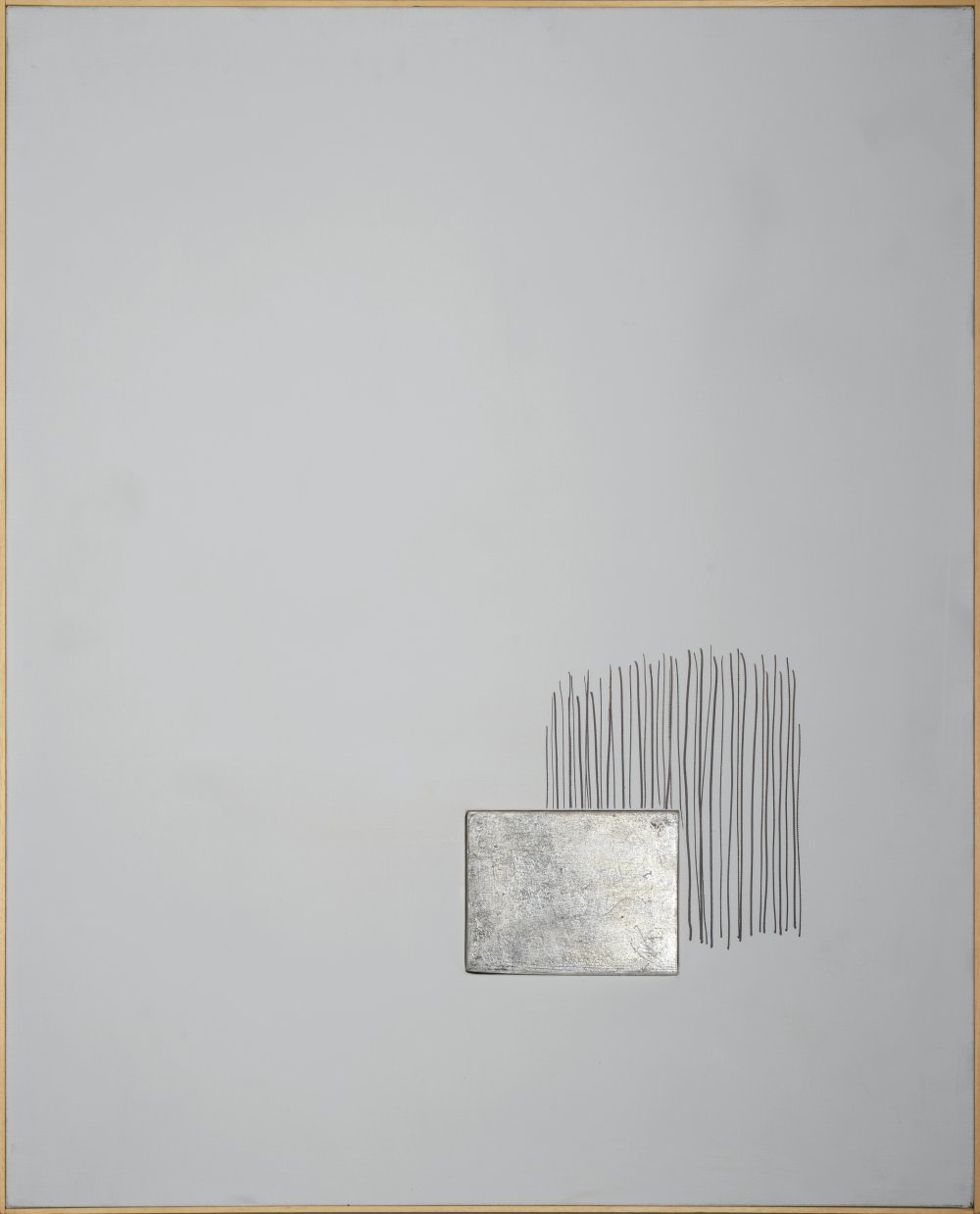

Invasione, 1976

Acrylic, silver leaf and wood on canvas

800.0 × 1000.0 mm

Registered at Archivio Arturo Vermi under “N67V211102H-1009”

Acrylic, marker pen, gold leaf and wood on canvas

810.0 × 1000.0 mm

Registered at Archivio Arturo Vermi under “D57P110705H-1916”

Approdo, 1977

Acrylic, silver leaf and wood on canvas

800.0 × 1000.0 mm

Registered at Archivio Arturo Vermi under “T77N181102H-1005”

Paesaggio, 1976

Tempera, marker pen, silver leaf and wood on canvas

800.0 × 1000.0 mm

Added to list

Done

Removed

ARTURO VERMI

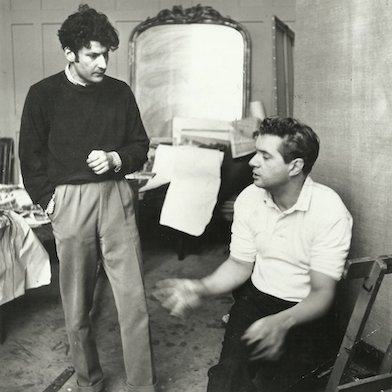

Arturo Vermi (Bergamo, 1928 – Paderno d’Adda, 1988) began producing sculpture in the 1960s and continued until the end of his career, albeit with increasing infrequency.

Although he debuted in 1956 with a solo show at the Centro Culturale Pirelli, Milan featuring descriptively figurative paintings influenced in particular by German Expressionism, he quickly changed tack. Indeed, just two years later, all trace of the figurative had disappeared from his work, the artist having immersed himself in Art Informel, an obligatory step towards the deep-felt reconstruction of a language open to the extraordinary social changes that were underway at the time.

In about 1960, Vermi spent two years in Paris. During that time, he came into close contact with the work of the Art Informel artists Dubuffet, Fautrier, Soulage and Poliakoff. But Paris was of course also home at that time to other artistic languages, including the Nouveau Réalisme concentrated around the critic Pierre Restany. While there, Vermi chose to focus exclusively on creating engravings, etchings and lithographs, which clearly left their mark on his subsequent work on the sign.

THE MILAN AVANT-GARDE AND THE CENOBIO GROUP

Then, as Vermi noted in his Lettera aperta (May 1983), he returned to “Milan, where the experimental ferment seemed to be more active and alive”. His period in Milan between the 1950s and 1960s was especially productive, thanks to the serendipitous simultaneous presence in the city of artists of high international importance. Led by the visionary example of artists like Lucio Fontana (1899–1968), a unique mix transformed industrious Milan into a formidable cultural laboratory. The incisive, innovative activity of Lucio Fontana and Bruno Munari (1907–1998), two of the most representative bridge figures in Italy, linked generations of otherwise distant artists and passed on experiences and knowledge, including that of Futurism, that were circulated in various ways. During that period, Milan not only regained its position of primacy but also became, to cite Angela Vettese, an “absolute forerunner in the sphere of western art.”

Arturo Vermi’s return to Italy coincided with the productive activity of the Cenobio Group, to which Brun Fine Art devoted an exhibition in October 2019: The Cenobio Group. Fontana, Manzoni and the Avant-garde.

The poet, philosopher and critic Alberto Lùcia was the glue between Ettore Sordini (1934–2012) and Angelo Verga (1933–1999), who had worked closely with Piero Manzoni (1933–1963), including experimentation with Arte nucleare. This trio of young artists enjoyed the support of Lucio Fontana, who presented their group show, “Manzoni, Verga, Sordini”, at the Galleria Pater in Milan on 29 May 1957.

Besides Vermi, other artists who joined the Cenobio Group were Agostino Ferrari (1938), a friend of Enrico Castellani (1930–2017), and Ugo La Pietra (1938), whose work was heavily concentrated in the area of planning and design led by Munari.

Both Sordini and Verga undoubtedly shared Manzoni’s passionate declaration that “the artist’s sole problem is that of attaining total freedom.” But theirs was a path that ultimately led them defend painting specifically against its possible negation. And so they moved in a direction that would be later described as semantic, aiming towards the reduction of the painting to a pure space of preliminary research on the sign. Their uninterrupted efforts laid the basis for foundation of the Cenobio Group in 1962, a collective that constituted the third face of the Milanese reaction to the crisis of Art Informel, the other two being the nihilism of Piero Manzoni and the objective/constructive approach of a large group of artists that included Castellani and Agostino Bonalumi (1935–2013).

“...in order to make this space-time void even more visible, I curved the surface so that the marks were like islands in the desert of time”.

THE SPACE-TIME CONTINUUM

Vermi absorbed Fontana’s lesson through their personal interaction and also though his reading of the older artist’s texts, which inspired reflection on the concept of space that led to the development of a wholly independent, original interpretation.

In the Diari series, he attacked the parameters that traditionally caged the artist and within which he was constrained to work, eliminating the surface and both physical and conceptual space. At the end of this initial angry path and tempestuous process concentrated on the foundational elements of painting, he found himself in a state of inner calm and was filled with an irrepressible need for silence.

And so, before the blank sheet of paper, the panic of horror vacui overcome, he perceived a reassuring space and entered the dimension of space that gratifies. Without deviations generated by the need to fill that space, he, as the artist described it in March 1971, began to “mark it with a silvery horizontal sign in the middle of a blue one or two signs in the middle of the whole empty sheet: the series I called Landscapes”. He gradually became aware that “space is such insofar as we are a point within it”. Then, developing his approach, “in order to make this space-time void even more visible, I curved the surface so that the marks were like islands in the desert of time”.

Vermi now piled up his theoretical breakthroughs, pouring them into paintings and sculptures, which became increasingly original and recognisable. In the arithmetic of his certainties, he acquired the rigorous figure of the quadrilateral and developed the sign as interpreter of the space for projection and that could now, through austere purification, take on the status of conceptual image.

Finally, wholly absorbed by manned space exploration, he satisfied his interest in the future life of humankind and the development of a humanity free from the constraints of the earth, engulfing his creativity in a spatiality that expanded into the infinite cosmic dimension.

His work, like that of the other former members of the Cenobio Group, continued to be grounded in commitment to a new form of painting that was regardless still painting and sculpture.

SUCCESS AND "EXILE"

Looking closely, as keenly observed by Tommaso Trini in 1974, it is almost impossible to distinguish between painting and sculpture in some of his work. Indeed, “the differential intersection of the genres, their mutual influence, has been current practice since the period of collage, used by Vermi, and that of Dadaist and Surrealist objects”.

And the sculptures presented by Vermi in 1974 at the Palazzo delle Prigioni Vecchie, Venice and in 1975 at the Rotonda in via Besana, Milan, were highly impactful. As observed by Luciano Caramel in 2018, these were “two extremely memorable exhibitions that won enormous acclaim among both critics and, aided by their unusually effective spectacularity, the public”.

But the firm establishment of the artist’s success was followed by a period of immense bitterness. As Vermi wrote in the Lettera aperta, “in 1975, I had an intuition that changed my life and work”. That was the year in which he wrote his “manifesto of disengagement” and had it posted up in three Italian cities. He also displayed it at his solo show at the Galleria Arte Struktura with two white panels next to it where visitors were invited to write, on one side, what they liked to do and, on the other side, what they did not like at all. After which, he was, in his words, “summarily judged by my exegetes and consequentially exiled”. Today, it is difficult to imagine stigmatising the search for happiness that inspired this declaration of disengagement. But in 1975, preaching to free oneself from all commitment to “father, mother, children, homeland, dogma, ideals, one’s word” in order to do “only what makes us happy” might have perhaps been perceived as subversive.

The Italian State had responded harshly, in 1968, to the construction of a 400-square-metre platform in the Adriatic Sea off the coast of Rimini (500 metres outside Italian territory) by a band of young people. The utopian attempt to create a micronation called Rose Island (with Esperanto as its official language) and, even more so, what it would have represented for many young people, was crushed by a blockade and later totally demolished. But if the annihilation of the little island, a dream easily shared by young Peter Pans all over the world, was little more than routine, Italy’s “Years of Lead”, a period defined by the attacks carried by the Red Brigades between 1974 and 1988, was another matter.

At a time marked by the armed conflict that reached its apex in 1978 with the kidnapping of the statesman Aldo Moro, Vermi’s words were probably perceived in entirely negative terms, hence, as the artist asserted, his exile, which ended only with his death in 1988, at the age of 60.

The paintings selected for this exhibition of Arturo Vermi’s work are united by the insertion of three-dimensional elements or surface application of two-dimensional elements. And so, within the category Inserts, to use Vermi’s own definition, we find paintings, made between the 1960s and late 1970s, that treat a variety of different themes. In some cases, the artist used collage, but he more often opted to insert pieces of wood covered with gold or silver leaf on the surface of the canvas, placing these physical, material elements in relation to his conceptual marks. The artist had an intense desire to seek, as he phrased it, not “absolute reality” but rather “the reality of humankind in relation to everything that surrounds it”, in a cosmic vision that, as Caramel observed, “allowed him to approach imminent transcendence”.

The Inserts were created alongside his activity as a sculptor, which led him to create the Platforms, Curved Surfaces and Fragments. But also the monumental sculpture that included the plan for a large Platform in the Sahara Desert, so that, in Vermi’s words, reported by Giorgio Brizio, “humankind will thus be able to unite with the sky, rising from the amorphous earth. With an extremely long run up, it will finally be able to reach other things, other lives to live or another kind of peace”.

The works displayed in Venice and Milan in 1974 and 1975 throw even more light on the symbolic/spiritualist vein that Vermi expressed through his sculptures, which is as a rule inherent to the natural, even if it contains a sacred transcendence in some cases. The artist often used gold and silver leaf as a powerful reference to astral light, graphite for the interstellar darkness and curved surfaces to evoke the curvature of the universe. Surfaces and materials that, in harmony with his register of cosmic visionariness, permitted him to achieve particular gradations of soft luminosity and fascinating light effects that unfurl their absorbing reference to something different. Key elements that distinguish this important part of his work. And so, in carving out cosmic spaces, Vermi imagined some of his panels arranged like installations in modern habitats, luminous rifts that can open up gaps in the space of the infinite universes and perceive, like powerful antennae, fragments of cosmos into which to project themselves.