Open: Tue-Sat 11am-7pm

Visit

Louise Bonnet: Onslaught

Gagosian, Hong Kong

Tue 31 May 2022 to Sat 6 Aug 2022

7/F Pedder Building, 12 Pedder Street, Central Louise Bonnet: Onslaught

Tue-Sat 11am-7pm

Artist: Louise Bonnet

There are all these rules about openings in the body, about things leaking out. That’s interesting to me—the body out of control.

—Louise Bonnet

Gagosian presents Onslaught, an exhibition of new paintings by Louise Bonnet that coincides with her inclusion in The Milk of Dreams at the 59th Biennale di Venezia, which opened on April 23. This is her first exhibition in Asia and comprises two groupings of three large canvases, displayed as triptychs.

Artworks

Oil on linen

1778.0 × 2134.0 mm

© Louise Bonnet. Photo: Jeff McLane. Courtesy Gagosian

Oil on linen

3658.0 × 2134.0 mm

© Louise Bonnet. Photo: Jeff McLane. Courtesy Gagosian

Oil on linen

1778.0 × 2134.0 mm

© Louise Bonnet. Photo: Jeff McLane. Courtesy Gagosian

Oil on linen

1778.0 × 2134.0 mm

© Louise Bonnet. Photo: Charles White. Courtesy Gagosian

Oil on linen

3658.0 × 2134.0 mm

© Louise Bonnet. Photo: Charles White. Courtesy Gagosian

Oil on linen

1778.0 × 2134.0 mm

© Louise Bonnet. Photo: Charles White. Courtesy Gagosian

Added to list

Done

Removed

Installation Views

In Onslaught, Bonnet focuses on corporeal fluids as objects of societal disgust, investigating art historical precedents for their depiction and considering the ways in which modern aesthetic and ideological conventions complicate the ways in which they are now received (“We are much more prudish about certain things now than people were in the 1500s,” she observes). The paintings explore our sense of mortification at our own bodies and the way they seem to betray us by leaking, sagging, or failing in various ways. “I’m interested in shame and the body in my paintings,” she states, “and bodily functions bring extra shame and embarrassment.”

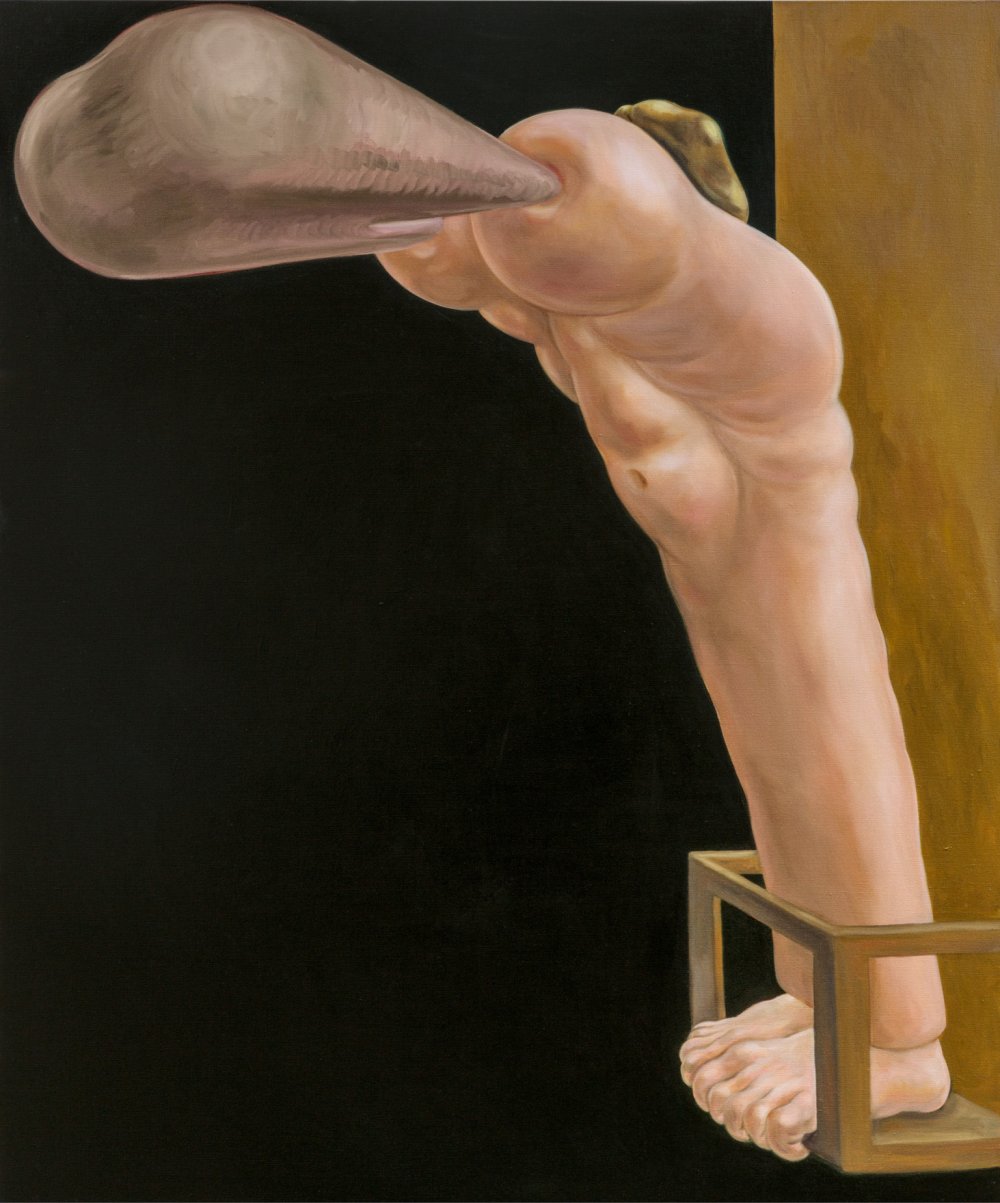

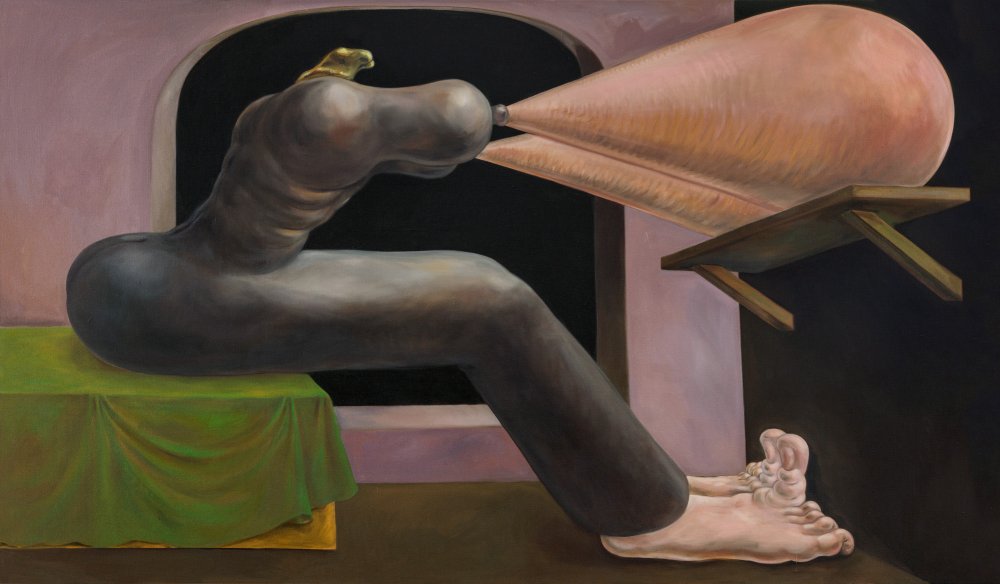

The first set of paintings in Onslaught depicts individual figures crouching or reclining awkwardly in confined interiors, their enlarged legs sheathed in colored pantyhose. The subjects of two compositions emit cones of opaque liquid, while the subject of a third lies on a bed, his or her tiny head veiled in a mop of blond hair. The figures in a second triptych also release vital fluid (presumably—in spite of its apparent rigidity—milk) from breast-like protuberances. The two figures that occupy the side panels teeter on small balconies while the central one’s toes are trapped beneath a wall. Bonnet’s pointed use of architectural devices exacerbates the images’ aura of physical and emotional isolation, recalling the oppressive, claustrophobic spaces of paintings by Francis Bacon.

While Bonnet’s compositions are steered by her irresistible sense of the absurd, their subtle color and light also display sensitivity to the formal and atmospheric possibilities of oil paint. Echoing sources from old masters such as Lucas Cranach the Elder and Caravaggio to modern iconoclasts Philip Guston and Cindy Sherman and, crucially, underground comix masters Robert Crumb and Basil Wolverton, she walks a fine line between beauty and ugliness, comedy and tension. Seemingly imprisoned in stark, cramped rooms, and further restricted by the edges of the frame, her cartoonlike protagonists act out dramas of profound physical and psychological discomfort, reflecting instinctual drives and anxieties.

Bonnet’s references for these paintings, which range from the antique to the contemporary, include sixteenth-century canvases and frescoes in which angels urinate on the crucified Christ, and in which Cupid relieves himself on Venus, as well as the Greek myth in which Zeus impregnates the imprisoned Danaë by taking the form of a golden shower (a phrase that now conveys a rather different meaning). A woman urinating, Bonnet has observed, is viewed very differently from a man engaged in the same act, when it can denote territorial power or irreverence (as in the phrase “pissing on your grave”).

More recent touchstones range from Mike Kelley’s Ectoplasm photographs of the late 1970s, which depict a paranormal substance pouring from the artist’s orifices, to Ken Price’s amorphous abstracted ceramic figures and the curiously sensual, figure-like machines of painter Konrad Klapheck. Even under their obscure and grueling conditions, Bonnet’s nameless, featureless characters direct their own unwieldy forms relentlessly toward the relief of stubborn urges. What remains pointedly uncertain is how their actions affect, or are affected by, our assumptions around the gendered, “othered” body.