Open: Tue-Fri 11am-6pm, Sat 11am-3pm

Visit

Lucy McKenzie & Atelier E.B

MEYER*KAINER, Vienna

Tue 13 Sep 2022 to Sat 29 Oct 2022

Eschenbachgasse 9, A-1010 Lucy McKenzie & Atelier E.B

Tue-Fri 11am-6pm, Sat 11am-3pm

Artists: Lucy McKenzie - Atelier E.B.

Curated by Karel Císař

Artworks

Fibreglass, acrylic and oil paint, belted silk dress, gym shoes

850.0 × 1450.0 × 670.0 mm

Fibreglass, acrylic and oil paint, silk dress with gold braid, gym shoes

600.0 × 1680.0 × 700.0 mm

Double sided folding screen in five parts, oil on canvas mounted on wood, silkscreen on cotton velvet mounted on wood, silkscreen umbrella accessory

3600.0 × 1600.0 × 65.0 mm

Double sided folding screen in five parts, oil on canvas mounted on wood, silkscreen on cotton velvet mounted on wood, silkscreen umbrella accessory

3600 × 1600 × 65 mm

Oil on wood, wooden structure, acrylic, textiles and mixed media

1200.0 × 1400.0 × 2200.0 mm

Atelier E.B., Lucy McKenzie and Beca Lipscombe

GUM, 2020

Oil painted, silkscreened and digitally printed fabric, acrylic painted wood panels and veneer on wooden structure

4000.0 × 3000.0 × 500.0 mm

V&A Paonazzo, De Ooievaar Chair & De Ooievaar Side table I, 2016, 2019 & 2016

Oil on canvas; wood, acrylic paint, textiles & wood, metal, trompe-l'oeil painting by Lucy McKenzie (oil on canvas on wood), stained veneer, glass

Painting: 72.5 x 52.5 cm, Chair: 87 x 45 x 45 cm, Ed. 10, Side Table: 44 x 40 x 40 cm

Wood, metal, trompe-l'oeil painting by Lucy McKenzie (oil on canvas on wood), stained veneer, glass

400.0 × 440.0 × 400.0 mm

Oil on canvas & Wood, acrylic paint, textiles

Painting: 52.5 x 62.5 cm; Chair: 87 x 45 x 45 cm, Ed. 10

Added to list

Done

Removed

Installation Views

The Scottish artist Lucy McKenzie mixes fine art painting practice with multiple collaborations in design, historic research and commerical fashion. The greatest manifestation of this is in her long term collaboration with the designer Beca Lipscombe in the company Atelier E.B. The present exhibition follows in the steps of a 2016 fashion presentation prepared by Atelier E.B, for Boltenstern.Raum Galerie Meyer Kainer. That antecedent clothing collection, called ‘The Inventors of Tradition II’, focused on the issue of expressing cultural identity by means of sportswear. Here, the present interest of McKenzie – both within Atelier E.B and independently − are the relationships between the pre-war haute couture and post-war Soviet fashion. This shift manifests itself not only in the historical and geographical difference of the sources of inspiration for the past and present projects but also in apparent details, such as the mannequins. Whereas six years ago, Atelier E.B presented its sportswear collection on schematic mannequins, McKenzie’s present artworks – which are copies of 1920s clothing desings of the French designer Madeleine Vionnet – are installed upon mannequins with heads of a real person, the very young guerilla fighter Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya, murdered in 1941 by the invading Wehrmacht and posthumously awarded the order of Hero of the Soviet Union. Her martyr’s death was commemorated by numerous public monuments, depicting Kosmodemyanskaya either as a combat-ready androgynous figure with a boyish haircut and in a skirt, or on the contrary as a harrowed female figure, scantly clad in torn petticoats and with her hands bound behind her back.

By presenting haute couture clothing on a mannequin with the face of a socialist war hero, Lucy McKenzie establishes a relationship between mutually opposite yet equally ideologically conditioned aesthetic regimes. Whereas in 1920s France, the bias cut introduced by Madeleine Vionnet represented a fashion revolution by freeing the female body as it did, in the 1940s Soviet Union it was taken for a sign of Western decadence. However, when the sculptors producing the historically later monuments of Kosmodemyanskaya wanted to emphasize her innocent victimhood they represented her in a flowing dress and barefooted, as did Vionnet with her models in her fashion shows. On the other hand, while Kosmodemyanskaya’s androgynous figure epitomized in the 1940s the ‘New Soviet Woman’, today similarly shaped figures, showing young people of vague gender and ethnicity, serve to sell the hypercapitalist ‘fast fashion’. McKenzie further underscored this ambivalence by choosing polychrome: the sitting figure is painted in a terracotta hue, commonly seen on classical Greek vases, whereas the standing figure is treated in aubergine, as known from Roman marble sculptures. The ambivalence was then heightened yet further by the artist’s choice of models to be reproduced, as their geometrical pattern can refer to ancient Greek architecture as well as to Soviet constructivist art.

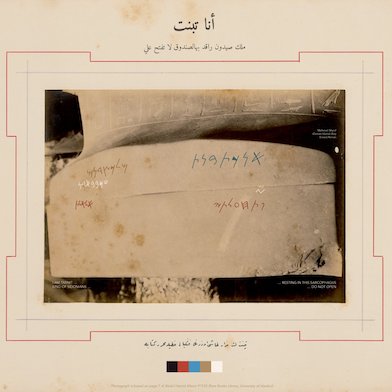

These contradictions, stemming from the ideological presuppositions of aesthetic ‘regimes’, are summarized by McKenzie in her 2021 work ‘Ethnic Composition (Moldova, Russian Ethnographic Museum)’. This is a replica of a map to be found in the Russian Ethnographic Museum in Saint Petersburg which defines the ethnic types of the population of Moldova on the basis of their traditional garb. However, the photographic illustrations from the original museum exposition were replaced by photos of other figurines, such as a mannequin exhibiting the traditional Jewish costume, a mannequin dressed as La Calavera Catrina on the occasion of the Mexican Day of the Dead, or a male figure illustrating the history of the Moscow department store GUM.

Whereas the terracotta-hued mannequin is looking out of the entrance of the gallery, the aubergine one, installed behind a separating panel, is turned inwards, as if imitating not only human proportions but also a person’s movement in space. It is wearily resting its back against the wall and looking over a paravent towards a vitrine with clothing. Since all three plastic installations have been produced in realistic dimensions and utilizing trompe l’oeil painterly techniques for imitating textiles, marble, wood and other materials commonly used in the interiors of modern fashion stores, the result is destabilizing both for our sense-perception, which is incapable of distinguishing what’s real and what’s painted, and for the character of the place we are in. At the same time, the installations refer to the complex history of mutual relationships between art and fashion and to the methods of their presentation.

In fashion environment, the function of the paravent is to protect the body from the gaze of passers-by. In our exhibition, it further serves – from the front – as the support for Lipscombe’s silkscreen depicting the cuts of the Jasperwear collection and – from the back – for McKenzie’s painting of a false terazzo depicting East Dunbartonshire landscape. The ‘Street Vitrine’, which holds the Atelier E.B products, installed by the trimmers Howard Tong and Barbara Kell, is a polemics with the surrealist objectification of the female body, as the artist avoids employing a mannequin and has the clothing installed dramatically by means of nylon threads. Yet at the same time McKenzie subverts the exclusivity of contemporary art, since the installation includes her own and Lipscombe’s off-the- rack models. Finally, the ‘GUM’ display, built for Atelier E.B by the artist and designer Steff Norwood, is a reconstruction – based upon McKenzie’s archival research – of the 1950s offer of fabric in the Moscow department store GUM, and with regard to the history of painting it further thematizes the classical relationships between the frame and the image, since the entire image here is merely the frame filled with random samples of fabrics.

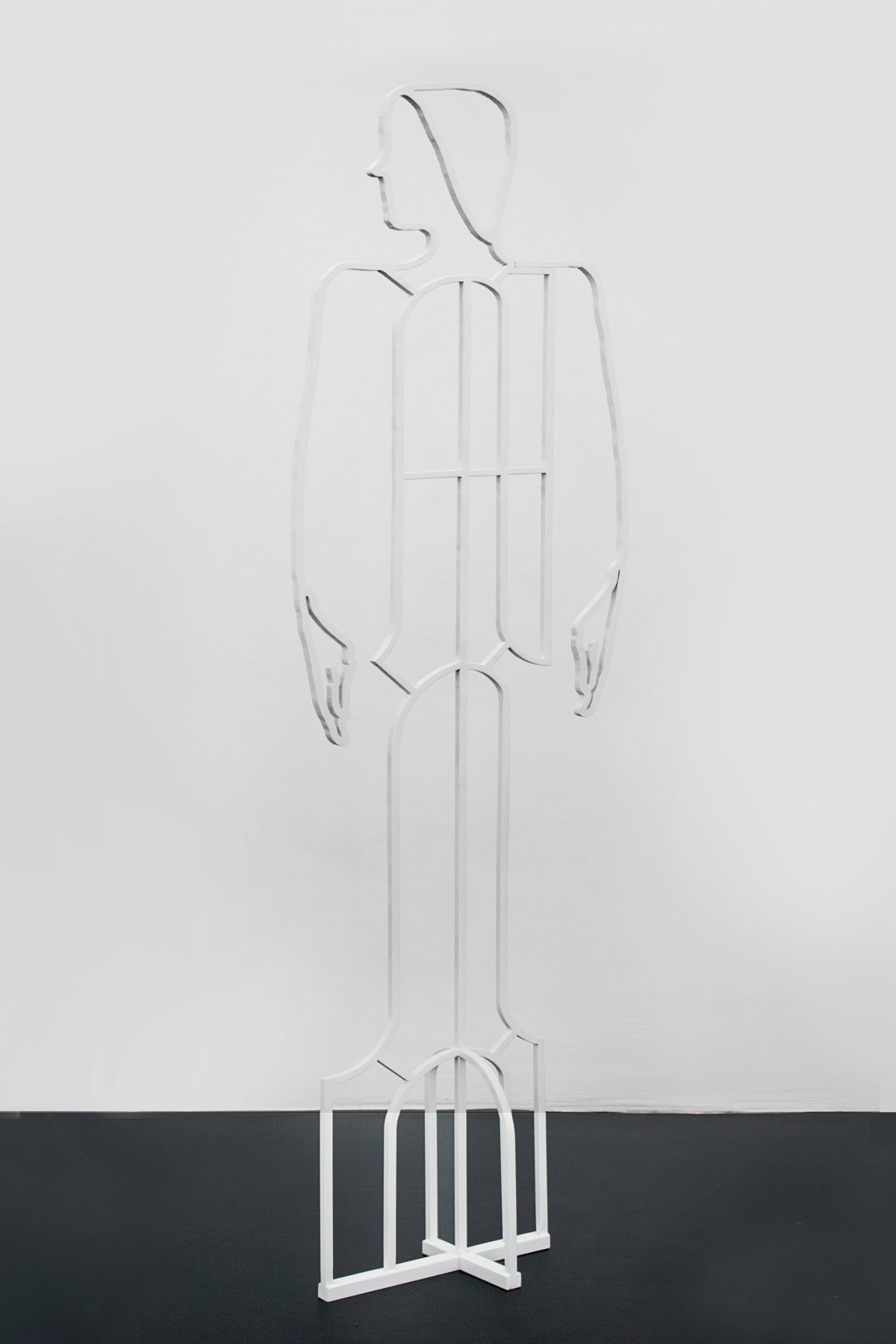

In contrast to the public manner the Atelier E.B production is installed in the main space, McKenzie’s presentation upstairs focuses upon the Villa de Ooievaar, a historically significant and officially protected building which the artist acquired in 2014 and whose reconstruction she pursues from that time. The modernist dwelling, called ‘The Stork Villa’ after the stork’s association with childbirth, was designed by the Flemish architect Jozef De Bruycker in 1935, in the era of growing authoritarianism in Europe. The villa, commissioned by a Catholic medical doctor for his 15-member family and his own medical practice, remained the family’s possession until the mid-1990s. Yet notwithstanding its private purpose, the villa’s interior is also marked by ideology, as it depicts stereotypes following from the definition of family as a basic societal unit, and its design adapts avant- garde notions to conservative and nationalist interests. Flemish nationalism is then referenced by McKenzie’s trompe l’oeil paintings, known as quodlibets, laid out under the glass tops of two round coffee tables and depicting objects relating to the villa , such as a memorial of Flemish nationalism, a postcard with a painting by the Belgian abstract artist Marthe Donas or a souvenir powder-box from the 1939 Glasgow Empire Exhibition. Even though the coffee tables and the replica of a chair were originally produced for standard use, they are presented in the exhibition not in immediate contact but rather upon a low pedestal, as used for exhibiting furniture in applied arts museums. These are complemented by two hanged paintings which include the motif of marble, the 2016 ‘V&A Paonazzo’ and ‘Bridge Club Breche II’ based on marble from the Vienna bridge club by Adolf Loos, which may give the appearance of a reconstruction of paintings contemporary with the building at the borderline of abstraction and decoration; yet in fact, these are the artist’s original works in which she resigned upon illusory depiction, and instead, captured the stone’s texture by means of pure, unmixed colors. The installation closes with an older metal mannequin and a display screen from Atelier E.B production; these stand here as autonomous plastic works, and in comparison with the mannequins’ realism appear almost like pictograms from a visual statistics. The exposition in its entirety establishes a phantasmagoric space which both destabilizes binary oppositions – such as fine and applied arts, individual creativity and collective design, or focused aesthetic contemplation and the browsing glance at shopwindows with fashion products – and discloses the ideological presuppositions of seemingly contradictory aesthetic (and other) regimes.

Karel Císař