Open: Tue-Sat 11am-7pm

Visit

Louise Nevelson

Mennour, 5 r. du Pont de Lodi, Paris

Artist: Louise Nevelson

Installation Views

Leah Berliawsky's life is a novel. An American novel. Born in 1899 in Ukraine, she migrated in 1905 with her mother, brother and sister to Maine in the United States, where her father had settled two or three years earlier. Little is known about her Ukrainian childhood except that she probably witnessed or escaped in extremis the pogroms that were decimating the Jewish community in the Russian Empire. From then on, her trajectory is consistent with an assimilation that would allow the young and now Americanised Louise to climb the social ladder – but not for long, given that her marriage in 1920 to Charles Nevelson, brother and business partner of a rich entrepreneur, soon proved a failure. Feeling cramped in her role as wife and mother, and struggling with the decline in social status that followed the financial setbacks of her husband's company, this increasingly emancipated woman set her sights on an artistic future.

In the 1920s this career was still in its infancy, with Nevelson as much attracted to the performing sphere – she enrolled at Frederick Kiesler and Norina Matchabelli's International Theatre Arts Institute, and immersed herself in the works of Martha Graham – as to the visual arts. However, an initiatory trip to Europe in 1931 to follow the teaching of, among others, Hans Hofmann in Munich, sealed her destiny as a visual artist, even if her way of envisaging the relationship between objects, space, and spectators invited to move in and around her future sculptures doubtless reflected kinaesthetic experiences deriving from her practices – she took dance classes until the 1950s – and reception in the field of choreography. This is one of the keys to Nevelson's work, which, unlike certain contemporary New York approaches, did not espouse the modernist credo of reducing her medium to its supposed essence while delimiting it. The fact that she resisted the dogmas of the New York school, with which she had a relatively conflictual relationship – a friend of Mark Rothko, she was scorned by the great prescriber Clement Greenberg – partly explains why she had to wait until she was sixty to make a name for herself.

A brief overview: after assisting Diego Rivera with his mural paintings in 1932– 1933, Nevelson, like many American visual artists, benefited from the WPA programme set up by the Roosevelt administration. This was an opportunity for her to teach, exhibit, and work free of financial anxiety and above all to familiarise herself with the rudiments of sculpture, thanks to state-subsidised workshops. It was not until 1935–1936 that Nevelson's name was identified with this medium, which she made her own a decade later, before finding her signature style in the second half of the 1950s. During this time, she had the chance to collaborate with influential New York dealers: Karl Nierendorf in the 1940s and Colette Roberts and Martha Jackson in the 1950s. It was with her exhibitions at the latter's gallery that Nevelson consolidated her trademark: sculptures produced from recycled scraps of wood, assembled and painted black, which helped make her one of the pioneers of the environment. Meanwhile her "walls", powered by an ingenious system of interlocking modules, gave her full control over the exhibition spaces made available to her while satisfying the "tailor-made" demands inherent in any location likely to host her sculptures. Thus, she had little interest in (re)defining a sculptural "object" in the specifically autarkic sense of her younger colleagues. All that mattered to her was the interaction generated by her assemblages with their surroundings and the atmosphere distilled by her play of light and shadow.

These priorities freed Nevelson from restrictive stylistic questions and enabled as required a move from a (pre)minimalist vocabulary and syntax to baroque outbursts fuelled by symbolic – or even narrative – elements integral to an individual mythology that was, admittedly, at odds with the prevailing trends of the 1960s. This decade marked the artist's real breakthrough. After a disastrous collaboration with Sidney Janis, she bet on a very young, all but unknown dealer, Arnold Glimcher, who had shown her in his Pace gallery in Boston in 1961. The rest is history. In the space of a few years, Nevelson, already praised by critics including Hilton Kramer, Brian O'Doherty, Michel Ragon and David Sylvester, and backed by major institutions – the Whitney gave her her first solo exhibition in 1967 after MoMA had associated her with group events and "invited" her to the Venice Biennale – became one of America's most important sculptors.

Encouraged by this belated success, she began venturing out of her comfort zone and exploring new avenues. Black-painted wood remained at the heart of her endeavours, but was now complemented by constructions in metal (for public commissions in particular), aluminium and plexiglass – and, of course, the collages she devoted herself to with such relish. The exhibition, which focuses on the 1970s, reveals the diversity of her production and the freedom and inventiveness Mrs. N (as her neighbours called her) displayed more than ever in the Final decades of her career.

— Erik Verhagen

Born in 1899 in Kiev, LOUISE NEVELSON died in 1988 in New York. A leading sculptor of the twentieth century, she pioneered site-specific and installation art with her monochromatic wood sculptures made of box-like structures and nested objects.

Nevelson emigrated with her family from czarist Russia to the United States in 1905, settling in Rockland, Maine. By 1920, she had moved to New York City, where she studied drama and later enrolled at the Art Students League. Throughout the early 1930s, Nevelson traveled across Europe and briefly attended Hans Hofmann’s school in Munich, returning to New York in 1932 where she studied once again with Hofmann.

Nevelson participated in several group shows throughout the 1930s, the first of which was organized by the Secession Gallery and held at the Brooklyn Museum in 1935. She received her first one-person exhibition at the Nierendorf Gallery, New York, in 1941—the first of several with the gallery throughout a decade punctuated by travels to Europe, explorations in printmaking, and work at the Sculpture Center in New York. By the late 1940s and early 1950s, Nevelson had traveled to Guatemala and Mexico to view Pre-Colombian art and began to produce a series of wood landscape sculptures.

An interest in shadow and space materialized in her first all-black sculptures, introducing a visual language that came to characterize much of her work from the mid-1950s onward. This development was encouraged in the form of acquisitions from three New York museums. In 1956, the Whitney Museum of American Art acquired Black Majesty (1955) and the following year the Brooklyn Museum acquired First Personage (1956). Soon thereafter, the Museum of Modern Art acquired Sky Cathedral (1958), further championing her work with the inclusion of Dawn’s Wedding Feast (1959) in the seminal group exhibition Sixteen Americans (1959–60). Nevelson had her first exhibition with The Pace Gallery, Boston, in 1961. Her representation was underscored by a brief affiliation Sidney Janis Gallery, New York, in 1962, which positioned her as the first sculptor and first female Abstract Expressionist within Janis’s roster and was followed representation by Pace in 1963 to the present. In 2018, the exhibition The Face in the Moon, was mounted at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, focusing on her work in drawing, printing, and collage, and spanning her progression from the human body into abstraction.

Nevelson’s compositions explore the relational possibilities of sculpture and space, summing up the objectification of the external world into a personal landscape. Although her practice is situated in lineage with Picasso’s Cubism and Vladimir Tatlin’s Constructivism, the pictorial attitude of her work and her interest in the transcendence of object and space reveal an affinity with Abstract Expressionism.

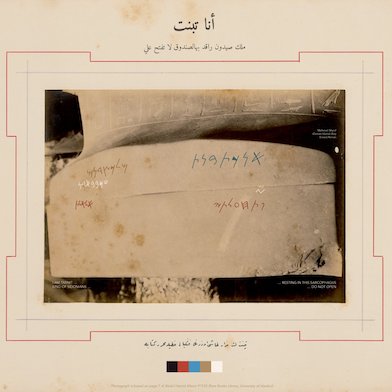

Exhibition views, « Louise Nevelson. Solo exhibition », kamel mennour (5 rue du Pont de Lodi, Paris 6), 2021

© ADAGP Louise Nevelson.

Photo. archives kamel mennour

Courtesy the artist; kamel mennour, Paris / London; Pace Gallery, New York / London / Hong Kong / Seoul / Geneva / Palo Alto / East Hampton / Palm Beach